Abies balsamea

Sponsor

Kindly sponsored by

Sir Henry Angest

Credits

Tom Christian (2021)

Recommended citation

Christian, T. (2021), 'Abies balsamea' from the website Trees and Shrubs Online (treesandshrubsonline.

Genus

Common Names

- Balsam Fir

- Balm-of-Gilead Fir

- Balsam

- Sapin Balsamier

- Balsamtanne

Infraspecifics

Other taxa in genus

- Abies alba

- Abies amabilis

- Abies × arnoldiana

- Abies beshanzuensis

- Abies borisii-regis

- Abies bracteata

- Abies cephalonica

- Abies × chengii

- Abies chensiensis

- Abies cilicica

- Abies colimensis

- Abies concolor

- Abies delavayi

- Abies densa

- Abies durangensis

- Abies ernestii

- Abies fabri

- Abies fanjingshanensis

- Abies fansipanensis

- Abies fargesii

- Abies ferreana

- Abies firma

- Abies flinckii

- Abies fordei

- Abies forrestii

- Abies forrestii agg. × homolepis

- Abies fraseri

- Abies gamblei

- Abies georgei

- Abies gracilis

- Abies grandis

- Abies guatemalensis

- Abies hickelii

- Abies holophylla

- Abies homolepis

- Abies in Mexico and Mesoamerica

- Abies in the Sino-Himalaya

- Abies × insignis

- Abies kawakamii

- Abies koreana

- Abies koreana Hybrids

- Abies lasiocarpa

- Abies magnifica

- Abies mariesii

- Abies nebrodensis

- Abies nephrolepis

- Abies nordmanniana

- Abies nukiangensis

- Abies numidica

- Abies pindrow

- Abies pinsapo

- Abies procera

- Abies recurvata

- Abies religiosa

- Abies sachalinensis

- Abies salouenensis

- Abies sibirica

- Abies spectabilis

- Abies squamata

- Abies × umbellata

- Abies veitchii

- Abies vejarii

- Abies × vilmorinii

- Abies yuanbaoshanensis

- Abies ziyuanensis

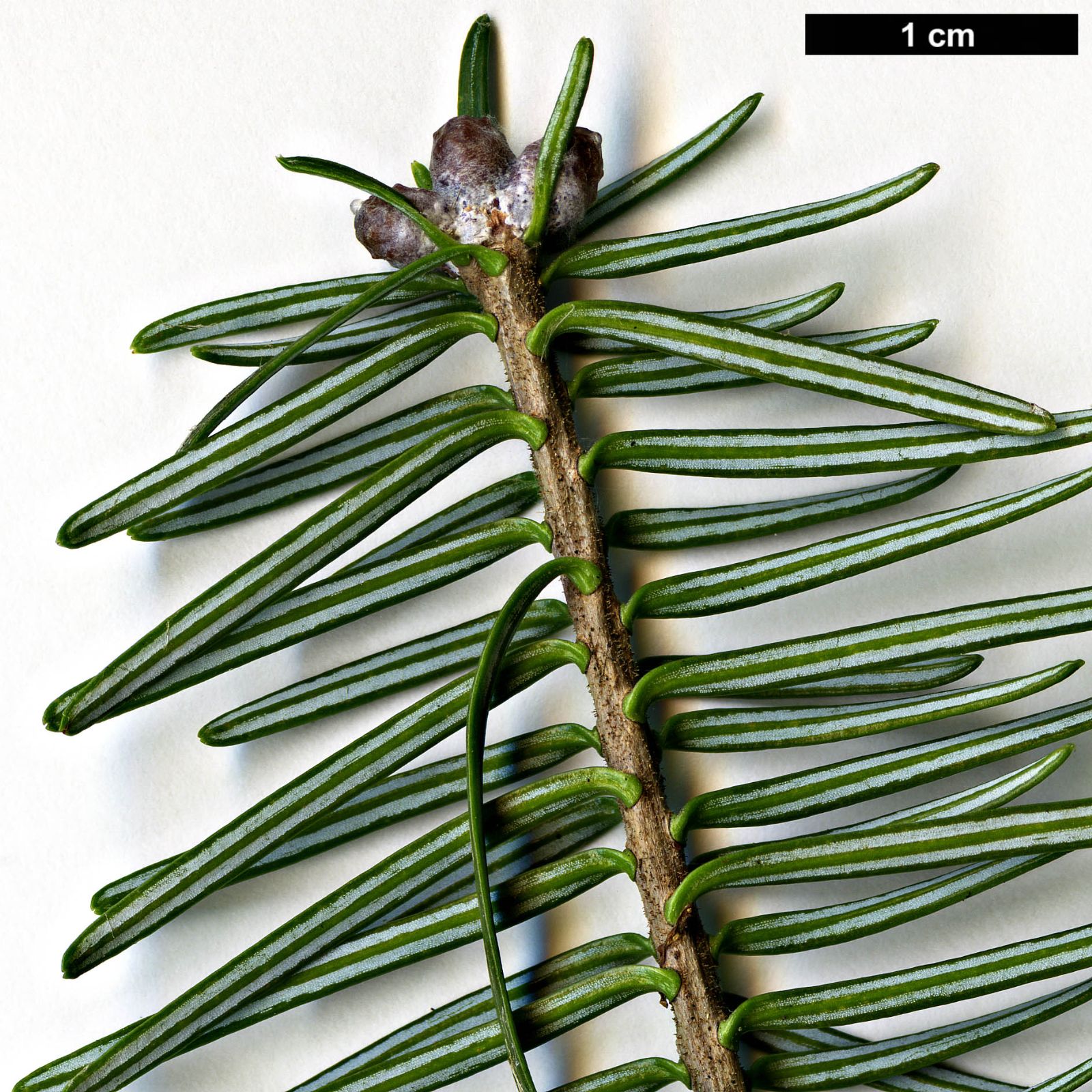

Tree to 25 m × 1 m dbh, or in some cases irregularly shrubby and decumbent. Crown conical-columnar. Bark in young trees pale grey, smooth, with prominent resin blisters; dark grey-brown or black-brown in old trees, flaking. First order branches long, slender, spreading more or less horizontally. Branchlets slender, pale yellowish-green, later pale grey, sometimes flushed red, smooth, with short pubescence of dark grey hairs. Vegetative buds ovoid to globose, c. 5 × 4 mm, resinous, with resin entirely covering the scales. Leaves more or less pectinate on lower branches, directed forward in the upper crown, (1–)1.5–2.5(–3) cm long, 2 mm wide, linear, base twisted, apex emarginate, dark green above with two white stomatal bands beneath, some stomata on the upper surface scattered along a medial groove, usually near the tips. The leaves release a strong, distinctive, resinous-balsam scent when crushed. Pollen cones crowded, pendant, 0.6 cm long, yellowish with purple microsporophylls. Seed cones (very) short-pedunculate to subsessile, cylindrical, apex obtuse, (2.5–)5–8 × (1.5–)2–3 cm, green, purple-tinted or violet-purple when immature, ripening to brown or purplish-brown; seed scales cuneate, flabellate, or rhomboid-orbicular, 1.2–1.4 × 1.4–1.7 cm at midcone; bracts included or sometimes with the cusp slightly exserted and recurved. (Farjon 2017; Debreczy & Rácz 2011).

Distribution Canada Alberta, Labrador, Manitoba, New Brunswick, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, Ontario, Quebec, Saskatchewan United States Connecticut, Iowa, Maine, Massechusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Vermont, Virginia, West Virginia, Wisconsin,

Habitat Over a vast range it occurs in a suite of habitat types, from lowland plains to mountains, and in coastal areas, 0–1200 m asl, most common on acidic, silty or sandy podzol soils. Near the cost the climate is cool-maritime, and inland cold-continental, characterised by very cold winters.

USDA Hardiness Zone 2-5

RHS Hardiness Rating H7

Conservation status Least concern (LC)

Abies balsamea is one of very few firs with a truly extensive natural range, occurring from Alberta east to Canada’s Atlantic coast, and across the Great Lake States and much of the northeast USA. It is also one of the most northerly occurring fir species in the world, at 57° N it is third only to A. sibirica and A. lasiocarpa (Debreczy & Rácz 2011). It is a valuable tree in North American horticulture, especially in colder areas, and Dirr advocates it for specimen plantings, groups, and Christmas tree production, but he cautions that it requires ‘well drained, moist, acid soils, and shelter from desiccating winds’ (Dirr 2011): like so many species utilised within their native ranges, Balsam Fir is more exacting in its requirements than might be assumed.

W.J. Bean berated Balsam Fir, declaring ‘It is among the biggest failures of firs in this country’ on account of its short-lived nature and that it ages rather disgracefully. Such wonderful words as ‘decrepitude’ pepper his account (Bean 1976). In the Supplement Clarke gingerly steps to Balsam Fir’s defence, explaining that it is a fir of smaller stature when seen in the context of the genus as a whole, and as such he suggests that ‘Its performance in the British Isles is therefore not so poor as might seem at first glance’ (Clarke 1988). Each of them is right, of course, and it does cause one to ponder what state a tree must have been in in 1891 when it was swept away in a flood, 194 years after it was planted at Saltoun, near Edinburgh, in 1697! We can trace this remarkable record to Alan Mitchell (Mitchell 1972) who offers no words of suspicion, yet no other cultivated Balsam Fir has come anywhere near matching the alleged Saltoun tree in age. Balsam Fir was certainly a very early introduction to cultivation, being introduced to Britain in the 1690s and to Norway in c. 1772 (Sudworth 1916). (Incidentally, Bean (1976) gives 1697, the same year the Saltoun tree is alleged to have been planted).

Many authors have observed that in youth they make very attractive trees, and young material in collections attests to this – in their first two to three decades they are shapely, conical trees. Bean noted that in their youthful stage they can grow ‘as well in south-eastern England as […] in Scotland’ (Bean 1976) and this remains the case. Jacobson (1996) doesn’t appear to share Dirr’s enthusiasm for the species, but notes that it is ‘widely planted anyway’. He also provides remarkable records of trees to 38 m tall in the wild, and to 35 m near Wanganui, New Zealand (Jacobson 1996).

Some wild plants can take on quite a shrubby, decumbent habit, due to the very harsh conditions that the species must contend with in various parts of its vast range, and several of these have been named and propagated over the years – the most prevalent are discussed below. This species is one of several that have been called Balm-of-Gilead. In North America its resin has been used medicinally, as a varnish, to seal birchbark canoes, and more recently as a glue to seal microscope slide cover slips (Jacobson 1996).

A. balsamea × A. fraseri

This cross can occur wherever the two species are grown together. The West Virginia Balsam Fir (A. balsamea var. phanerolepis) is still often considered to represent such a hybrid (written as A. × phanerolepis) but there is sufficient evidence now that this is not the case, and no binomial exists for a hybrid Balsam × Fraser Fir. It is becoming best known in North America under the selling name for a race of Christmas trees, A. FRALSAM™ which Larry Hatch feels sure is likely to become a desirable subject in the landscape in years to come, for it combines the best qualities of both parents, producing a neater, denser, bluer tree than both (Hatch 2021–2022).

'Andover'

A slow-growing form with no apical dominance, ultimately a wide-spreading plant. First found in Andover, New York (Auders & Spicer 2012).

'Caerulescens'

A short-leaved form, ultimately a small tree, with prominent stomatal banding on both leaf surfaces. Raised in France c. 1865 by Sénéclauze (Auders & Spicer 2012).

'Columnaris'

A vigorous selection raised in Germany c. 1903, with a dense columnar habit and very short leaves (Auders & Spicer 2012).

Dwarf Cultivars

Due to the extreme environment in large parts of its range, many wild trees of A. balsamea are naturally stunted or otherwise dwarf. Many such plants have been propagated, as have selections of witches’ brooms from wild and cultivated trees. This has led to a surfeit of dwarf selections, often with few or no points of significant difference except independent origins. Of these the Hudsoniana Group (or ‘Hudsoniana’) is the most widespread; it is discussed separately. So too is ‘Nana’, also widespread, which differs in the radial arrangement of its leaves. The following distinguish themselves as described; most remain <3 m in ten years, with those described as ‘extreme dwarf’ typically remaining less than 50 cm in ten years:

- ‘Albicans’ Young leaves whitish

- ‘Argentea’ Glaucous or whitish leaves

- ‘Bear Swamp’ Cushion-forming extreme dwarf

- ‘Bruce’s Variegated’ Slow growing form with leaves variegated golden-yellow

- ‘Cree’s Blue’ Leaves strongly glaucous, irregular dwarf habit

- ‘Cree’s Blue’ Leaves strongly glaucous, irregular dwarf habit

- ‘Cuprona Jewel’ Cushion-forming extreme dwarf

- ‘Densa’ Compact, somewhat fastigiate

- ‘Denudata’ Compact, somewhat contorted habit, sparsely branched

- ‘Elegans’ Leaves radially arranged

- ‘Henksgarden WB’ Extreme dwarf with yellowish leaves

- ‘Jamy’ Extreme dwarf with pale green leaves

- ‘KBN Variegated’ Cream-white variegated leaves, eventually a small tree but very slow

- ‘Kiwi’ An extreme dwarf

- ‘Krause’ Another extreme dwarf

- ‘Larry’s Weeper’ A narrow weeping clone that requires staking to the desired height

- ‘Le Feber’ A low mound with yellow-green needles, to 50 × 100 cm in ten years

- ‘Little Carleigh’ An extreme dwarf

- ‘Longifolia’ An old clone of upright habit said to have leaves longer and narrower than typical

- ‘Lutescens’ With leaves pale yellow or buff when young, later green

- ‘Marginata’ Leaf margins yellowish

- ‘Nudicaulis’ A very sparsely branched clone

- ‘Old Ridge’ Conical habit with young leaves creamy yellow

- ‘Piccolo’ Extreme dwarf

- ‘Prostrata’ Extreme dwarf wider than tall

- ‘Quinton Spreader’ Extreme dwarf wider than tall

- ‘Renswoude’ Extreme dwarf with pale green leaves, a mutation of ‘Nana’

- ‘Sticky Fingers’ An upright to columnar dwarf with unusually long branchlets and short, resinous needles

- ‘Treehaven Dwarf’ Almost an extreme dwarf, upright, to 60 × 30 cm

- ‘Variegata’ With leaves white-variegated, ultimately a small tree

- ‘Verkade’s Prostrate’ A slow-growing shrubby selection very similar to ‘Hudsoniana’ but mat-forming

- ‘Walcott Pond’ Somewhat upright dwarf tree, ultimately taller than broad

- ‘Yellow Tips’ Leaves with golden-yellow apices, ultimately a small tree

(Auders & Spicer 2012; Hatch 2018–2020).

'Eugene Gold'

Synonyms / alternative names

Abies balsamea 'Eugene's Gold'

Abies balsamea 'Eugene's Yellow'

With golden-yellow leaves. A very compact dwarf at first, spreading initially but after many years a small upright tree. Raised in Vermont before 1995 (Auders & Spicer 2012).

'Fastigiata'

Raised at Armintrout’s Nursery in Michigan during the 1980s (Auders & Spicer 2012); other means of distinction from ‘Columnaris’ are unknown.

Hudsonia Group

Synonyms / alternative names

Abies balsamea f. hudsoniana (Jacques) Fern. & Weatherby

Variably written as a stand-alone cultivar, a cultivar group, or (rarely now) as a forma, we have opted to follow the Royal Horticultural Society and treat this as a Cultivar Group, which although loosely defined may be used to incorporate those dwarf shrubby selections that are ultimately wider than tall and somewhat flat topped. Many of the selections listed under ‘Dwarf Cultivars’ fit this definition, but are not always singled out in other works.

Auders & Spicer (2012) use this name as a stand-alone cultivar and make a further distinction by pointing out that the leaves are conspicously parted above the shoots (cf. ‘Nana’, in which they are more radial). Edwards & Marshall (2019) note that the original clone was found in the White Mountains of New Hampshire, USA, and introduced to cultivation prior to 1810.

'Nana'

Very similar to Hudsoniana Group selections, differing only in the radial arrangement of the needles (Auders & Spicer 2012).

'Tyler Blue'

An unusual form with pale blue leaves that makes a small, compact tree. Found as a chance seedling in a New Hampshire Christmas tree plantation (Auders & Spicer 2012). Larry Hatch praises it, suggesting it “[leaves] nothing for blue spruces to brag about” (Hatch 2021–2022) but he cautions that seed-raised plants may be masquerading as the genuine clone in commerce.

var. phanerolepis Fernald

Common Names

Canaan Fir

West Virginia Balsam Fir

Synonyms

Abies intermedia Fulling

Abies balsamea f. phanerolepis (Fernald) Rehd.

Abies × phanerolepis (Fernald) T.S. Liu

Abies balsamea subsp. phanerolepis (Fernald) E. Murray

Distinguished from the type by the exserted bracts of the seed cone, with long, reflexed cusps. (Farjon 2017).

Distribution

- North America – Its full distribution is poorly known but it has been reported from Quebec, south to West Virginia and Virginia.

RHS Hardiness Rating: H7

USDA Hardiness Zone: 4

Taxonomic note For some time this variety was thought to be a hybrid between A. balsamea and A. fraseri, and while it is possible that some hybrid forms do occur where the two species meet in the Southern Appalachians, this has not been proven. Furthermore trees matching var. phanerolepis have been found to occur in natural populations of A. balsamea well to the north of the northern limits of A. fraseri. (Farjon 2017, Debreczy & Rácz 2011).

This variety is a good example of a well named taxon: its name is derived from the Greek phaner- (conspicuous) and lepis (scale), in reference to the exserted bract scales of the seed cones. Although it has been recognised since 1909, even at the end of the 20th century Jacobson (1996) observed that it is generally not distinguished in North America, neither in forestry nor horticulture. It has gradually come to prominence in recent decades, though, after attracting the attentions of the Christmas tree industry, though it remains largely overlooked as an ornamental (Bates 2017).

The earliest significant introduction to the UK took place quite recently, when Chris Reynolds and Dan Luscombe of Bedgebury Pinetum introduced it in 2006 under the number CRDL 41. It was introduced prior to this at least once, with trees known from the Yorkshire Arboretum (now dead) and White House Farm thought to date from the very late 1980s (O. Johnson pers. comm. 2021). The CRDL collection was made in Canaan Valley State Park in West Virginia, at an altitude of nearly 1000 m asl. The field notes tell us it was growing with Acer rubrum, Picea rubens and Tsuga canadensis, but perhaps most interestingly they go on to say ‘The ground is very boggy pH 3.5 to 5.0’ which gives an insight as to the species’s tolerance of harsh growing conditions. This collection has been widely planted; Bedgebury distributed excess material to a broad range of UK collections, some via the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, and there are now excellent examples growing in such diverse sites as Lael Forest Garden near Ullapool in the far north west of Scotland, Dawyck Botanic Garden in Peebleshire, Bicton Park Botanical Gardens in Devon, and of course at Bedgebury itself. A tree at Ashmore House, Perthshire, Scotland, was coning by 2019 only six years after planting (pers. obs. 2019). Material from this collection is also growing in continental European collections, including le Jardin des Plantes de Paris and Arboretum Wespelaar.