Corylus avellana

Sponsor

Kindly sponsored by

Kent Men of The Trees

Credits

Owen Johnson & Richard Moore (2023)

Recommended citation

Johnson, O. & Moore, R. (2023), 'Corylus avellana' from the website Trees and Shrubs Online (treesandshrubsonline.

Genus

Common Names

- European Hazel

- Nocciolo Comune

- Avellano Común

Infraspecifics

- 'Anaconda'

- 'Anny's Purple Dream'PBR

- 'Anny's Red Dwarf'

- 'Aurea'

- 'Burgundy Lace'®

- 'Contorta'

- 'Contorta Purpurea'

- 'Fuscorubra'

- 'Little Rob'

- 'Pendula'

- 'Purple Umbrella'TM

- 'Red Dragon'®

- 'Red Majestic'PBR

- 'Rotblättrige Zellernuss'

- selections for nut production

- 'SKCORY19SCOOB'

- 'Twister'

- 'Urticifolia'

- var. pontica

- 'Variegata'

Other taxa in genus

- Corylus americana

- Corylus americana × avellana

- Corylus avellana × cornuta

- Corylus avellana × heterophylla

- Corylus avellana × maxima

- Corylus avellana × sieboldiana

- Corylus avellana × sutchuenensis

- Corylus Badgersett Hybrids

- Corylus chinensis

- Corylus colchica

- Corylus colurna

- Corylus × colurnoides

- Corylus cornuta

- Corylus fargesii

- Corylus ferox

- Corylus 'Grand Traverse'

- Corylus heterophylla

- Corylus jacquemontii

- Corylus maxima

- Corylus 'Purple Haze'

- Corylus 'Rosita'

- Corylus 'Ruby'

- Corylus sieboldiana

- Corylus × spinescens

- Corylus sutchuenensis

- Corylus 'Te Terra Red'

- Corylus × vilmorinii

- Corylus yunnanensis

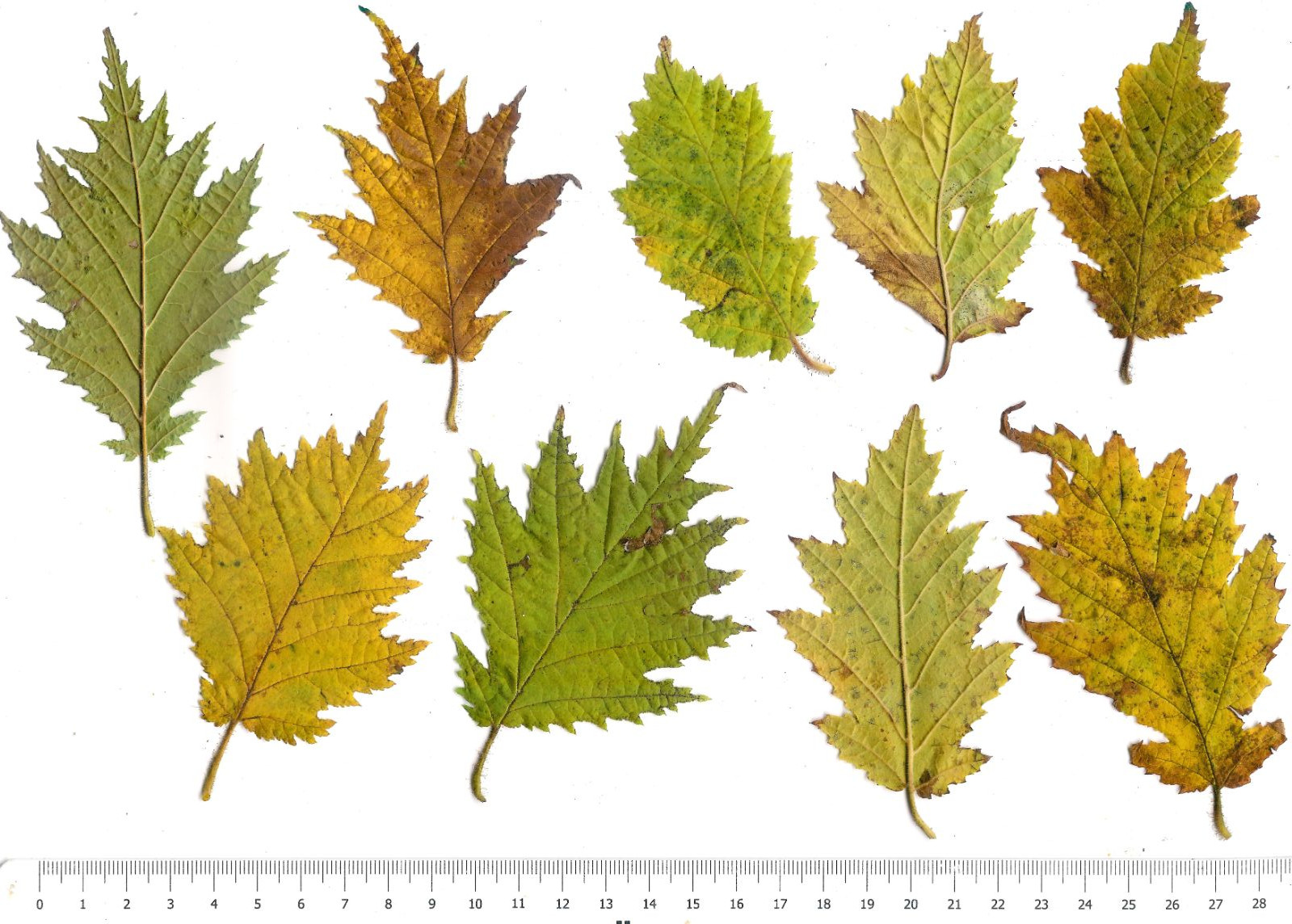

Shrub or small tree, to 15 m, continually producing new stems from the base. Bark bright pale brown, rather smooth, sometimes with a few finely shredding papery rolls, and distantly fissured in age. Young twigs with rather long and stiff glandular hairs. Leaf 5–12 × 4–12 cm, rounded to obovate, narrowly cordate to rounded at the base, tip abruptly acuminate, margin coarsely double-toothed to lobulate, finely pubescent on both surfaces; petiole short (6–12 mm), with rather stiff glandular hairs. Male catkins usually in clusters of 2–4, to 8 cm long; peduncles usually 5–12 mm long. Nuts in clusters of 2–4, large (c. 18 mm long); bracts spreading, scarcely longer than the nut, pubescent, the margin deeply and irregularly lobed but not greatly pleated. Flowering January–March; nuts ripening August–September. (Bean 1981; Furlow 1997).

Distribution Albania Andorra Armenia Austria Azerbaijan Belarus Belgium Bosnia and Herzegovina Croatia Cyprus Considered introduced by some authorities Czechia Denmark Including Faroe Islands Estonia Finland In the far south France Including Corsica Georgia Germany Greece Probably not native to Crete Hungary Iran Probably native near the Caspian Sea Ireland Italy Including Sardinia and Sicily Kosovo Latvia Liechtenstein Lithuania Luxembourg North Macedonia Moldova Montenegro Netherlands Norway Poland Portugal Mostly in the north Romania Russia European Russia, except in the north and the far south Serbia Slovakia Slovenia Spain Mostly in the north Sweden In the south Switzerland Syria Probably native to mountains in the north Turkey Mostly in the north Ukraine United Kingdom

Habitat Woodlands, except on very acid, very wet or very chalky soils; scrub; open land in humid regions.

USDA Hardiness Zone 6

RHS Hardiness Rating H6

Conservation status Least concern (LC)

The European hazel is one of that continent’s most abundant and ubiquitous trees. It is not hardy enough to grow in the coniferous forests of northern Russia and northern Scandinavia, and is confined to moist microclimates towards the Mediterranean; it is absent from acid heaths, riverine woods and chalk downland. (In southern England it is often a feature of woodlands over chalk, but here there is typically a thin surface layer of acid clay, to which hazel’s shallow roots are confined. Hazel is often recommended as a plant for chalky soils, but this is a slight misrepresentation: it will survive in such conditions, but rarely luxuriate.) The broad soft leaves, held in level tiers and often remaining green into early winter, are a feature equipping hazels to flourish as an understorey plant in mature woodland, in which role it is often dominant, but the species can be quick to colonise abandoned grassland, and always fruits better when it gets some sun. The shallow roots are not drought-tolerant and the thin bark is vulnerable to sun-scorch, making this more exclusively a woodland plant towards the south of its natural range. Being wind-pollinated, hazel pollen is abundantly represented in prehistoric deposits: the pollen record shows that it was one of the first trees to move north in the wake of the last glaciation, and for a few thousand years it may have become the commonest woody species in more Oceanic climates.

Young hazels quickly begin to produce a series of fast-growing wands from around the base. (Unlike the two North American hazel species, the European tree produces these from just above ground level, so it stretches the meaning of the word to call them ‘suckers’.) As the oldest stems begin to rot and collapse, a selection of the new wands will be reaching maturity, in a process than can theoretically continue ad infinitum. It is very rare to see a dead or dying hazel across most of its natural range, and stools that get blown over or crushed by falling trees just continue to grow their new stems. Consequently, many of the individual hazels in an ancient wood can reasonably be assumed to be many hundreds of years old, if not thousands. The largest and oldest single trunks are found where wood-pasture grazing pressure prevents the new shoots from developing; one such tree just north of Loch Arklet in the Great Trossachs Forest region of the Scottish Highlands, first recorded in 2007 by Peter Quelch, has a dbh of 80 cm (Tree Register 2023).

A significant pest of Corlyus avellana in Great Britain is the introduced North American grey squirrel, Sciurus carolinensis. Rather than waiting until the nuts ripen and then burying a proportion for future use (and allowing new plants to grow when the nut gets forgotten), grey squirrels tend to strip hazels of their nuts when these are still green. Authorities such as the late Oliver Rackham have suggested that this behaviour will make hazel a threatened plant in Britain (Rackham 2006), although some young hazels can still be seen even in places where grey squirrels have become abundant.

The straight, flexible young poles lend themselves for basketry, hurdle-making, the manufacture of thatching spars, the stakes and binders for laid hedges, and the wattles used in traditional house building in many parts of Europe. This, combined with the tasty nuts, made hazel one of the most useful of wild plants, a status reflected in the tree’s prominence in Celtic mythology. A strong wrist can even turn a two- or three-year old wand into an ersatz rope, by twisting it to separate the fibres. Hazel produces an excellent firewood, burning with a faint toffee smell. It was also the traditional wood for a diviner’s rods; the roots could be used as a yeast substitute in the brewing process (Bean 1981). Its natural way of growing new sprouts may even have inspired early foresters to manage other broadleaved trees in this fashion within coppice woodlands.

With its long golden to ochre catkins in late winter, the pale yellow of its falling leaves at the very end of the year, and the bronze burnish of its younger trunks, a hazel can be a quietly attractive tree, though the development of woodland gardens in Britain in particular through the twentieth century depended on extirpating the often hazel-dominated understorey of existing woods so that rhododendrons and other shade-loving plants could be grown instead. Its very ubiquity as a wild plant probably discourages the use of unselected hazels, either as a garden plant or as subjects for a botanic collection. In North America, by contrast, C. avellana has been planted quite widely as an ornamental, at the expense of the two native species (Furlow 1997).

Hazel’s role as a nut producing tree does give it a dual landscape role, in pleached allées and the nutteries which can be features of gardens as formal as Sissinghurst Castle (UK), and within which the hazel trees can be underplanted with shade-tolerant herbacious ornamentals. In southern and eastern Europe, and in Turkey towards the Black Sea, commercial hazelnut orchards can be large-scale landscape features.

Hazels selected for their fruit, and long grown across Europe, often have significantly longer husks than wild C. avellana: it is clear that more than one taxon was involved prehistorically in the development of these clones, but not at all clear what the other species was, or were. This issue is discussed further under the entry for C. maxima, below. For convenience, and irrespective of the length of the husk, all the most important clones that have been bred for nut production in Europe and the Near East are grouped here as C. avellana × maxima. Most of the European hazels selected as ornaments have short husks and do seem to be simple sports of C. avellana; two purple-leaved hazels with longer husks are listed here as cultivars of C. maxima, as is conventional. The list of cultivars below, consequently, includes only the ornamental selections.

'Anaconda'

A new, more upright and vigorous variant of the popular corkscrew hazel, ‘Contorta’ (Bluebell Arboretum and Nursery 2023).

'Anny's Purple Dream'PBR

A very compact clone with an upright habit and rather small, slightly glossy leaves which flush purple and fade to brownish-green; raised in the Netherlands and released in 1999. The catkins are pale mauve, but the plant is shy to flower (Hatch 2021–2022; Royal Horticultural Society 2023; Edwards & Marshall 2019).

'Anny's Red Dwarf'

Synonyms / alternative names

Corylus avellana 'Anny's Compact Red'

A dwarf form with a dense upright habit (but not quite as compact as ‘Anny’s Purple Dream’; purplish leaves fade to reddish green. Any nuts are reddish brown (Hatch 2021–2022; Royal Horticultural Society 2023). ‘Anny’s Red Dwarf’ is represented in the very extensive hazel collection at the Sir Harold Hillier Gardens in England (Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh 2023).

'Aurea'

Common Names

Golden Hazel

A sport with yellow young leaves which fade steadily to the rather dark, dull green characterictic of Corylus avellana, first described from Germany in 1864 (Petzold & Kirchner 1864). In cultivation in the UK it is slightly more vigorous than the wild species, reaching 11 m with stems 47cm thick by 2019 at the Thorp Perrow Arboretum in Yorkshire (Tree Register 2023). This vigour, and the bark which is greyer than usual for the wild hazel, might suggest that this plant is better placed under C. maxima, although no authorities seem to have treated it as such; the husks are significantly longer than the nut, though they do not conceal it as the tips are deeply and jaggedly lobed.

The extensive hazel collection at the Sir Harold Hillier Gardens also includes ‘Ashburnham Gold’ and ‘David’s Golden Marvel’, neither of which yet seem to be in commerce (Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh 2023).

'Burgundy Lace'®

The first hazel to combine purple and dissected leaves is a product of Oregon State University’s Agricultural Experiment Station at Corvallis, where hazels are bred for commercial nut production and resistance to Eastern Filbert Blight (EFB). Released in 2015, ‘Burgundy Lace’® has quickly become popular in the United States: although it is pure Corylus avellana it is claimed to show good resistance to EFB, and also to produce tasty nuts in modest quantities. Like the other purple sports of C. avellana, the leaves fade steadily to bronzy-green (Mehlenbacher, Smith & McCluskey 2018).

'Contorta'

Common Names

Corkscrew Hazel

Harry Lauder's Walking-stick

Synonyms / alternative names

Corylus avellana 'Contorta Pendula'

Awards

AGM

‘Contorta’ is perhaps the most satisfying of those plants whose twigs and leaves contort and curl crazily. In summer, the dark twisted leaves are dull, but the bronze sheen of the young stems lends them a sculptural quality, and their weird twists contrast delightfully with the plumb lines of the catkins which open in spring (later than most wild Corylus avellana). The sport still sold commercially was discovered in a hedgerow near Frocester in Gloucestershire, England around 1863 and transplanted to the Earl of Ducie’s arboretum at Tortworth Court (Bean 1981). Bowles (1914), in whose “Lunatic Asylum” of mutant plants it was the ‘first crazy occupant’, records that Ducie ‘increased it by layering, and so distributed it to a few friends’. Bowles’s own plant was a sucker from one of these and this early practice of layering seems likely to be the source of older non-grafted plants – for example an old-looking plant in the walled garden at Crathes Castle in Aberdeenshire (though it has been suggested that ths represents an independent mutation (C. Pirnie pers. comm.)). Unfortunately the usual practice of grafting usually results in the production of abundant straight basal growth that needs to be pruned out. Hazel cuttings are not easy but the plant can be layered or stooled successfully and this should be practiced more frequently when propagating Corylus cultivars.

Novelty walking-sticks made from the wood of ‘Contorta’ were popularised by the Scottish singer Henry MacLennan (1870–1950), whose stage name was Harry Lauder.

Top-grafted plants, in which the twisted stems tend to hang rather than ascending, are sometimes sold in North America under the illegitimate name ‘Contorta Pendula’ (Hatch 2021–2022). In that continent, ‘Contorta’ is always liable to succumb to Eastern Filbert Blight.

'Contorta Purpurea'

A form combining contorted growth with purple leaves (fading to bronzy-green). Plants of this kind are now quite widely sold as ‘Red Majestic’PBR, a clone originating in 1997, but one nursery (The Tree Garden Kent) advertises ‘Contorta Purpurea’ (The Tree Garden Kent 2023) and another (Beech Grove Nursery in Northern Ireland) offers ‘Contorta Purpurea’ and ‘Red Majestic’PBR separately (without describing any differences; Beech Grove Nursery 2023). The dendrologist Tony Titchen also grew a plant as ‘Contorta Purpurea’, and gifted one to the Tortworth Court collection in Gloucestershire (the first home of ‘Contorta’ itself.) Its latinate form means that to be a valid name, ‘Contorta Purpurea’ would have to have been described before 1959; we have not found any records this old for its cultivation, and the name may be illegitimate.

'Fuscorubra'

See under ‘Rotblättrige Zellernuss’ below.

'Little Rob'

A dwarf hazel whose small leaves flush red-purple and fade to bronzy-green, originating at the André van Nijnatten nurseries, Netherlands (Encyklopedia Drzew 2023) and now popular in eastern Europe.

'Pendula'

Common Names

Weeping Hazel

A very weeping plant, usually top-grafted, which was exhibited by the Niessing nursery at the World Exhibition in Paris in 1867 and quickly became popular across Europe (Holstein, Tamer & Weigend 2018; Bean 1981). The big broad leaves make this less graceful as a weeping tree than some, through summer at least, and like most pendulous sports it is shy to flower. The greyish bark and general vigour of the stocks of some old trees in Britain suggest that it was customary to graft ‘Pendula’ onto plants best called Corylus maxima; one at Fanhams Hall in Hertfordshire has a trunk 53 cm thick, while the example in the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh was planted as long ago as 1918 (Tree Register 2023).

'Purple Umbrella'TM

A weeping hazel whose rather rugose leaves open rich purple before fading to reddish-green (Edwards & Marshall 2019; Hatch 2021–2022); selected by Jósza Miklós in Hungary (Szkółka Szmit 2023).

'Red Dragon'®

One of several hazel clones combining purple foliage with contorted growth, ‘Red Dragon’ is a product of Oregon State University’s hazelnut breeding programme, arising in 1997 and patented in 2010 (Oregon State University 2023). Like other purple hazels, the colour quickly fades to bronzy-green, but ‘Red Dragon’® is quite resistant to Eastern Filbert Blight in North America (Hatch 2021–2022).

See also ‘Contorta Purpurea’ and ‘Red Majestic’PBR.

'Red Majestic'PBR

Awards

AGM

A hazel that tries to do everything: compact, with contorted and weeping stems and purple young leaves; ‘Red Majestic’ was raised by Rolf de Vries in Germany in 1997 – the same year as its New World equivalent and rival, ‘Red Dragon’® (Hatch 2021–2022). The largest of three at John Ravenscroft’s Cherry Tree Arboretum in Shropshire, UK, was 4 m tall in 2021 (Tree Register 2023).

See also ‘Contorta Purpurea’.

'Rotblättrige Zellernuss'

Common Names

Red Hazel

Red Avaline

Blood Hazel

Synonyms / alternative names

Corylus avellana 'Purple Avalon'

Corylus avellana 'Purpurea'

Corylus avellana 'Red Zellernut'

Corylus avellana 'Rode Zellernoot'

Corylus avellana 'Rote Zeller'

Corylus avellana 'Rotter Zellernuss'

Corylus avellana 'Red Zellernut'

Corylus avellana 'Rote Zellernuss'

Corylus avellana 'Rouge de Zeller'

Corylus avellana 'Red Zellernuss'

Corylus avellana 'Rotter Zellernuss'

Awards

AGM

A cultivar, or a group of cultivars, with purple young leaves soon fading to bronzy-green, pinkish catkins and reddish nuts in dark red husks which are no longer than the nut itself. Hazels of this sort have been grown both as garden features and for nut production; in the former role they are always likely to be eclipsed by the plant generally known as Corylus maxima ‘Purpurea’, which is slightly more vigorous and whose leaves hold their purple colour well. (The latter cultivar is conventionally placed within C. maxima because its husks are much longer than the nut.) It should be noted than one oddity of many wild C. avellana is a central blotch of purplish anthocyanins, which quickly fade to green; the patch is most obvious on later leaves in full sun, and is irregular in shape with sometimes sharp edges. C. sieboldiana, a rather distantly related hazel from north-eastern Asia, can show the same feature.

A ‘Rotblättrige Waldnuss’ was first described by Franz Göschke in 1887 from the arboretum of Reinhardt Behnsch near Wrocław (now in Poland; Holstein, Tamer & Weigend 2018); this plant was described as Corylus avellana f. fuscorubra by Leopold Dippel three years later. The treatment of the clone by W.J. Bean in Trees and Shrubs Hardy in the British Isles implies that by the early twentieth century it was generally known as C. avellana ‘Purpurea’ in the UK; Bean recommended ‘Fusco-rubra’ (sic) since the name C. avellana var. purpurea had been used by J.C. Loudon to describe the plant now known as C. maxima ‘Purpurea’ (Bean 1981). Holstein, Tamer and Weigend, in their contemporary taxonomy of the genus Corylus, also recommend the use of ‘Fuscorubra’ (Holstein, Tamer & Weigend 2018), while RHS prefers ‘Purpurea’ (Royal Horticultural Society 2023).

Descendants of the original ‘Rotblättrige Waldnuss’ may now be almost extinct in gardens; three old plants accessioned as ‘Fuscorubra’ at the Sir Harold Hillier Gardens had all gone by 2017 (Tree Register 2023). These scions were probably bound, in any case, to get submerged within the fruiting selections which have probably long been cultivated around Europe under a variety of names which translate roughly as ‘Red Hazel’ or ‘Blood Hazel’. Both the Royal Horticultural Society and the Hillier Manual of Trees and Shrubs recommend the use of the German name, ‘Rotblättrige Zellernuss’ (Royal Horticultural Society 2023; Edwards & Marshall 2019), perhaps by assocation with Göschke’s original ‘Rotblättrige Waldnuss’. The former resource implies that the differences between this ‘vernacular’ form and Göschke’s garden plant are certainly very subtle (‘red’ rather than ‘pinkish-purple’ young leaves); it might be easiest to group all these plants as representatives of the one red-leaved variant. (In German, ‘Waldnuss’ implies a wild hazel, while ‘Zellernuss’ is a cultivated, fruiting tree; another name for this group is ‘pontische Nuss’, implying Turkish origins, while ‘Zellernuss’ refers to the monastery of Zell near Würzburg where such plants were long grown (Unser Garten 2023).) At the United States’ National Clonal Germplasm Repository at Corvallis, Oregon, plants grown as ‘Fusco-rubra’ are smaller than those grown as ‘Rode Zeller’, with thinner rather drooping shoots, smaller catkins and a lighter red pigmentation (Smith & Mehlenbacher 2002).

Under whatever name, red hazels remain popular, combining as they do the qualities of a satisfactory nut tree with a degree of ornamental interest in early summer. With their vulnerability to Eastern Filbert Blight, the group has probably never been grown much in North America; in North American Landscape Trees, Arthur Lee Jacobson states that a weak-growing plant of this sort was known as ‘Purple Avalon’ around 1974 (while wrongly placing ‘Rote Zeller’ as a clone of Corylus maxima; another sale-name in America was ‘Red Fortin’, used for a short-husked hazel with red leaves fading to bronzy-green which was found in the abandoned orchard of a French immigrant, Mr Fortin, in Washington State. Another clone found in the same orchard, ‘Fortin’, had longer husks and probably represented C. maxima ‘Frühe van Frauendorf’ (q.v.; Jacobson 1996).

selections for nut production

All of these are grouped for convenience under the heading Corylus avellana × maxima.

'SKCORY19SCOOB'

Synonyms / alternative names

Corylus avellana 'Scooter'®

A dwarf variant of ‘Contorta’ (Royal Horticultural Society 2023), though the stems are less ‘madly’ contorted; more noteworthy perhaps is the fact that the internodes are short, causing the plant to be congested, and in winter to present a dense mass of leaf buds. ‘Scooter’® is of Dutch origin (Vida Verde 2023) and a specimen sourced on the Continent by Ullrich Fischer was planted at the Yorkshire Arboretum, UK, in 2019 (Yorkshire Arboretum 2023; T. Baxter pers. comm.).

'Twister'

A dwarf variant of ‘Contorta’, similar to ‘Scooter’ and expected to grow 1.5 m tall (Royal Horticultural Society 2023).

'Urticifolia'

Common Names

Cut-leaved Hazel

Synonyms / alternative names

Corylus avellana 'Heterophylla'

Corylus avellana 'Incisa'

Corylus avellana 'Laciniata'

Corylus avellana 'Pinnatifida'

Corylus avellana 'Quercifolia'

Sports of the wild hazel whose rather smaller leaves are deeply cut into narrow, jagged lobes have been grown under a variety of names through the last two centuries. In English-speaking countries this mutation is likeliest to be known as ‘Heterophylla’, following its description from Loddiges’ Nursery by J.C. Loudon (as Corylus avellana var. heterophylla) in Arboretum et Fruticetum Britannicum (Loudon 1838). In their recent taxonomic checklist of the genus, however, Holstein, Tamer and Weigend point out that the earliest and therefore correct name is ‘Urticifolia’, published in France in 1825 (Holstein, Tamer & Weigend 2018). Neither moniker is particularly apt (‘Heterophylla’ means ‘with leaves of varying shape’ but the lobing of these variants is relatively consistent; ‘Urticifolia’ means ‘nettle-leaved’), and for many British gardeners and suppliers this tree will probably still be known as ‘Heterophylla’ for years to come. But one significant consideration in recommending the use of ‘Urticifolia’ is that it prevents confusion with the Chinese species C. heterophylla, a hazel with an important place in contemporary nut breeding but a shadowy presence at best in western gardens. As of 2023, plants sold by European nurseries as C. heterophylla can be assumed with fair confidence to represent C. avellana ‘Urticifolia’ instead – even when the nursery has the impeccable botanical credentials of Pépinière des Avettes.

‘Urticifolia’ is not particularly rare in cultivation, though it may seem to be so since, unlike for example the fern-leaved beech (Fagus sylvatica ‘Aspleniifolia’) the lobed leaf does not result in a particularly eye-catching plant; it is as a curiosity that this tree is likely to be grown. The mutation is due to a single recessive gene (Mehlenbacher & Smith 1995) and is likely to occur quite frequently. A specimen that still grows on the Colesbourne estate in Gloucestershire, UK, is said to have been found and transplanted to its current site by the great dendrologist Henry Elwes around the start of the twentieth century; other English examples likely to be of independent origin include a very old tree at Litchborough Hall in Northamptonshire with a stool 1.5 m wide at the base, and one reported by Peter Bourne in 1996 from Whitelands Wood in the High Elms Country Park, south-east London (Tree Register 2023). In common with other mutant hazels, this form has the minor demerit of being sparing in its production of showy, male catkins in late winter.

var. pontica (K. Koch) H.J.P. Winkl.

Synonyms

Corylus pontica K. Koch

Corylus colurna var. glandulifera (K. Koch) A. DC.

Corlyus imeretica Kem.-Nath.

Corylus pontica var. glandulifera K. Koch

Described as a plant with fruit-bracts significantly longer than the nut, doubly-toothed and prominently veined (Holstein, Tamer & Weigend 2018).

Distribution

- Turkey – Described as native to the north of the country by some authorities.

RHS Hardiness Rating: H6

USDA Hardiness Zone: 5

This elusive taxon provides one possible ancestor for the proportion of cultivated European hazelnuts whose bracts are significantly longer than the nut itself (see also Corylus maxima and C. colchica). Some of these ancestors must have come from the eastern part of the natural range of C. avellana; the ancient Roman author and naturalist Pliny the Elder refers to a ‘nux Pontica’ whose origins were supposed to have been in Turkey, south of the Black Sea (Holstein, Tamer & Weigend 2018).

A ‘Corylus pontica’ was described in 1849 by the German botanist Karl Koch from this same part of Turkey, which he had visited in 1843–4. There are no surviving herbarium specimens from this time, and Koch writes merely of a plant like C. avellana but showing the elaborately lobed bracts of C. colurna, which is also native to this region (Koch 1849). The taxon is accepted by some authorities (including Plants of the World Online) as a variety of C. avellana with doubly-serrate and prominently veined bracts (Holstein, Tamer & Weigend 2018); this is a feature exhibited by some fruiting hazels such as ‘Tombul Ghiaghli’ (a Greek variant of the old Turkish ‘Tombul’) (Erdogan & Mehlenbacher 2000). In Georgia, the fruiting clone ‘Tita’ is also considered to represent var. pontica (Kharabadze et al. 2023). However, other authorities such as Y.J. Nasir in Flora of Pakistan (Nasir 1976) treat Koch’s name as a synonym for C. colurna. (As a straight-stemmed tall tree with a corky fissured bark, C. colurna is instantly separable in the field by even the most casual observer, but none of these distinguishing features remain available to the desk-bound taxonomist. The leathery, elaborately frilled bracts of C. colurna are also quite different in the hand from those of any C. avellana variant.)

A few plants are grown in western collections under the name Corylus avellana var. pontica, including a mature bush five metres tall in the Sir Harold Hillier Gardens (19774119*R) which lacks accession details (Tree Register 2023); Jan De Langhe observes that these can have slightly more lobulate leaves than is typical for C. avellana (De Langhe 2016). A specimen in the Steere Herbarium of the New York Botanical Garden, collected in 1992, is now a twig without leaves or fruit (New York Botanical Garden 2023). In their monograph on Corylus, Holstein, Tamer and Weigend reasonably conclude that ‘the persistence of a “pure” genotype of “var. pontica” in the wild (if it ever existed) is more than doubtful.’ (Holstein, Tamer & Weigend 2018).

'Variegata'

Common Names

Variegated Hazel

A variegated hazel was first described by Alphonse de Candolle in 1864 (Holstein, Tamer & Weigend 2018). What is likely to represent the same sport was still sold until very recently in (Ukraine); the leaves have a bold creamy-white variegation, leaving central splashes of green. Just as the leaves flush, the variegation is reddish.