Lindera obtusiloba

Sponsor

Kindly sponsored by

a member of the International Dendrology Society

Credits

Julian Sutton (2023)

Recommended citation

Sutton, J. (2023), 'Lindera obtusiloba' from the website Trees and Shrubs Online (treesandshrubsonline.

Infraspecifics

Other taxa in genus

- Lindera aggregata

- Lindera akoensis

- Lindera angustifolia

- Lindera assamica

- Lindera benzoin

- Lindera chienii

- Lindera communis

- Lindera erythrocarpa

- Lindera floribunda

- Lindera fragrans

- Lindera glauca

- Lindera megaphylla

- Lindera melissifolia

- Lindera metcalfiana

- Lindera neesiana

- Lindera praecox

- Lindera pulcherrima

- Lindera reflexa

- Lindera rubronervia

- Lindera sericea

- Lindera tonkinensis

- Lindera triloba

- Lindera umbellata

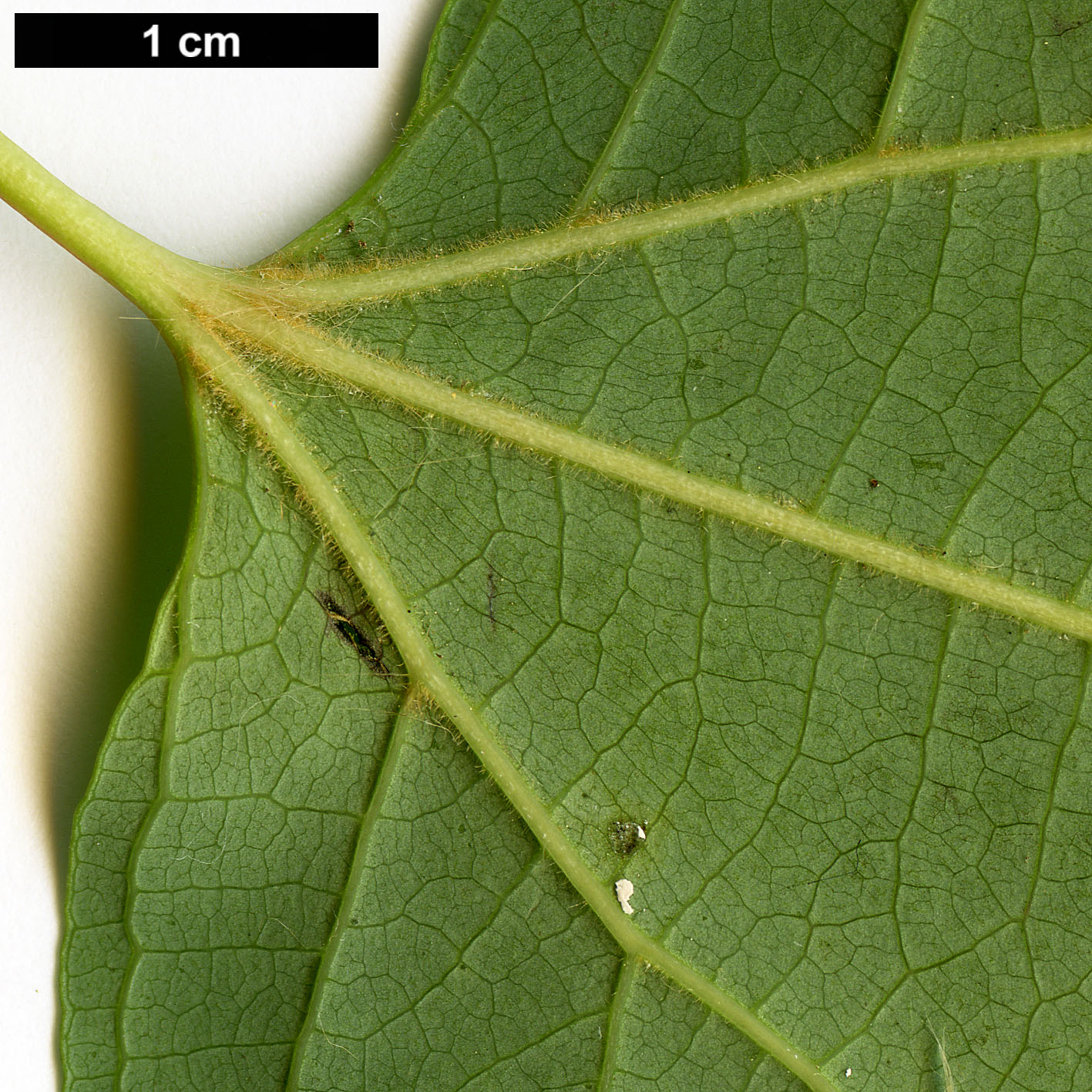

Deciduous shrub or small tree to 10 m. Bark brown to black. Young branchlets yellow-green, smooth. Buds ovate, apex acuminate; outer bud scales 3, yellow-brown, elliptic, 6–9 × 6–7 mm, leathery, glabrous; inner bud scales 3, with dense yellow-brown silky hairs; flower and vegetative buds sometimes enclosed within a single bud, sometimes seperate. Leaves trinerved; blade suborbicular to elliptic, usually 3-lobed, sometimes unlobed or with 5 lobes, 5.5–10 × 5–11 cm; lower surface pale green (sometimes reddish), yellow-brown-pubescent at last at first; upper surface darker green; base cuneate, rounded or cordate; margin usually entire, sometimes wavy; apex acute to rounded; petiole 1.5–3 cm, pubescent. Flowers in sessile, 5-flowered umbels. Flowers with 6 narrowly elliptic tepals, males with 9 stamens. Fruit red at maturity, ageing purple-black, ellipsoid, 8 × 5–6 mm. Flowering March–April (China), January–April (Britain); fruiting August–September (China). (Cui & van der Werff 2008; Bean 1981).

Distribution Bhutan Myanmar China Anhui, Fujian, S Gansu, Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Jiangsu, Jiangxi, S Liaoning, S Shaanxi, E Shandong, Sichuan, Xizang, NW Yunnan, Zhejiang India Japan North Korea South Korea Nepal

Habitat Forests and thickets in valleys and on mountain slopes; near sea level to 3000 m.

USDA Hardiness Zone 6-9

RHS Hardiness Rating H6

Awards AGM

Conservation status Least concern (LC)

Probably the best known lindera in European gardens, L. obtusiloba is also one of the finest. It usually forms a large, multistemmed shrub, worth growing both for flowers and its bold foliage. Like most linderas it suits moist but well-drained soil, in full sun or part shade. While sometimes said to require acidic soil, it is often found on limestone mountains in China (Lancaster & Rix 2019).

With its trinerved, usually 3-lobed, deciduous leaves, Lindera obtusiloba could only be confused with L. triloba. L. triloba is readily distinguished from L. obtusiloba by its glaucescent leaf undersurface, and acuminate tips to the lobes. Lobing is usually shallower in L. obtusiloba. L. triloba has larger fruits which split irregularly into 5 or 6 segments to reveal the seed (Ohwi 1965). The two species have a similar range in Japan, but L. obtusiloba extends much further, into Korea, China, and through Myanmar to the Himalaya. Interestingly, a molecular study did not support a close relationship between L. obtusiloba and other trinerved species, although L. triloba was not included (Tian, Ye & Song 2019). Along with most other linderas, L. obtusiloba has had uses in traditional medicine; its therapeutic potential might be linked to antioxidant properties (Haque et al. 2020).

Flowers emerge from conspicuous rounded winter buds before the leaves, in late winter or early spring, the timing varying a great deal between seasons in the mild climate of South Devon, UK (pers. obs. 1998–2023). In Pennsylvania, Bunting (2021) finds it flowering usefully between the last Hamamelis and the first cherries and magnolias. The flowers are a rather sharp shade of yellow, ‘the colour of newly made mustard’ (Edwards & Marshall 2019), and like other linderas attract whatever insects are flying at the time, mainly flies and bees. The fruits – red, ultimately black – are an added attraction, contrasting well with yellow autumn foliage (Thomas 1992), but witnessed by few gardeners. This is a dioecious, sexual species, so males and females must be grown together for fruit set. Few seem to bother with this, but there is a reliably fruiting population at Hergest Croft, Herefordshire, UK (Lancaster & Rix 2019).

In typical forms most leaves are 3-lobed, although some are usually unlobed, especially near the bases of extension shoots (pers. obs.). Both leaf outline and the shape of the base are quite variable, within and between plants. Forms of the species with usually unlobed leaves have proved taxonomically troublesome (see below); rare in gardens, they can be distinctive and attractive. Newly emerged leaves are sometimes bronzed or purple-flushed. Butter-yellow is the most familiar autumn colour – the discerning Michael Dirr (2009) claims that he knows ‘no other woody shrub that rivals it for intensity of yellow’. Some plants age brilliantly red or orange (see images). A much-photographed plant in Roy Lancaster’s Hampshire (UK) garden is one of these; it derives from a collection made by Seijo Yamaguchi (Honshu, 1998 as L. triloba), distributed to Westonbirt and perhaps elsewhere under L 2166 (R. Lancaster pers. comm. 2023).

The species was described from Japan by Blume (1851). His specific epithet has since proved misleading: while the leaf lobes may have obtuse or rounded apices, they can also be acute (but never acuminate as in L. triloba). It was introduced to European gardens in 1880 by Charles Maries collecting for the Veitch nursery (Bean 1981); whether as seed or living plants, from Japan or China, is unknown, since Maries sent material in both ways and moved quite frequently between China and Japan during the 1870s (Veitch 1906). Other early introductions from Japan to the Arnold Arboretum were by Charles Sargent (1892 and 1919) and by John Jack in 1905 (Arnold Arboretum 2023). Bean (1981) mentions Ernest Wilson collecting Chinese material for the Arnold in 1907–8 (presumably under W 301 and/or W 3690 and 3691 from Hubei, or W 3692 from Sichuan – Sargent 1916); none of these, however, appear in the catalogue today (Arnold Arboretum 2023). There have been numerous subsequent introductions by western expeditions and through botanic garden seed exchanges, notably from the Chollipo Arboretum, S Korea.

Lindera obtusiloba is reasonably hardy at the Atlantic margin of Europe. Larger, older specimens are scattered across England, with a strong southerly bias; interestingly, at least half the specimens recorded by The Tree Register (2023) are of unlobed forms labelled as or suggested to be ‘cercidifolia’ or ‘praetermissa’ (see below), which are generally considered uncommon. Perhaps these represent one or more particularly large-growing early collections. In the short, cool summers at Howick Hall on the Northumberland coast, this is the only Lindera species which has really thrived (pers. obs. 2022), from several Japanese collections. In Scotland there are plants from BBJMT 224 (C Honshu, 2005) at RBG Edinburgh and milder Logan (Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh 2023). In Belgium it is recorded from Arboretum Provinciaal Domein Bokrijk, Arboretum Kalmthout and Arboretum Wespelaar (Plantcol 2023).

Dirr (2009) considers it worthy of wider planting in North America, where it has proved long-term hardy in both Atlantic and Pacific coastal States and Provinces (Arnold Arboretum 2023; US National Arboretum 2023; University of California Botanical Garden 2023; Hoyt Arboretum 2023; University of British Columbia 2023). At the Missouri Botanical Garden, St Louis, with its more extreme summer and winter temperatures, all recorded accessions have died, whether planted out or in greenhouses (Missouri Botanical Garden 2023).

Forms with unlobed leaves have prompted a confusing series of names over the years, none of which is usually recognized at species level today. They are nicely summarized by Lancaster & Rix (2019). Both L. cercidifolia Hemsl. and L. praetermissa Grierson & D.G.Long are treated as synonyms of typical L. obtusiloba in Flora of China by Cui & van der Werff (2008), who could find no correlation between lobing and supposed differences in leaf hairs, and by Plants of the World Online (Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew 2023). More than a century ago, Wilson found the distinction between L. obtusiloba and L. cercidifolia ‘obscure’ (Sargent 1916). L. heterophylla, with silky golden hairs on the young leaves, and a westerly wild range, is still recognized as L. obtusiloba var. heterophylla (see below). These three names are repeatedly applied – seemingly at random – to unlobed plants in British gardens. A stock grown at Westonbirt and elsewhere, reputedly from F 29087 (provenance frustratingly unknown) has been labelled as all three in different places at different times; it seems to belong in L. obtusiloba var. heterophylla (Lancaster & Rix 2019). It should be stressed, though, that unlobed plants without such hairs belong in the type var. obtusiloba.

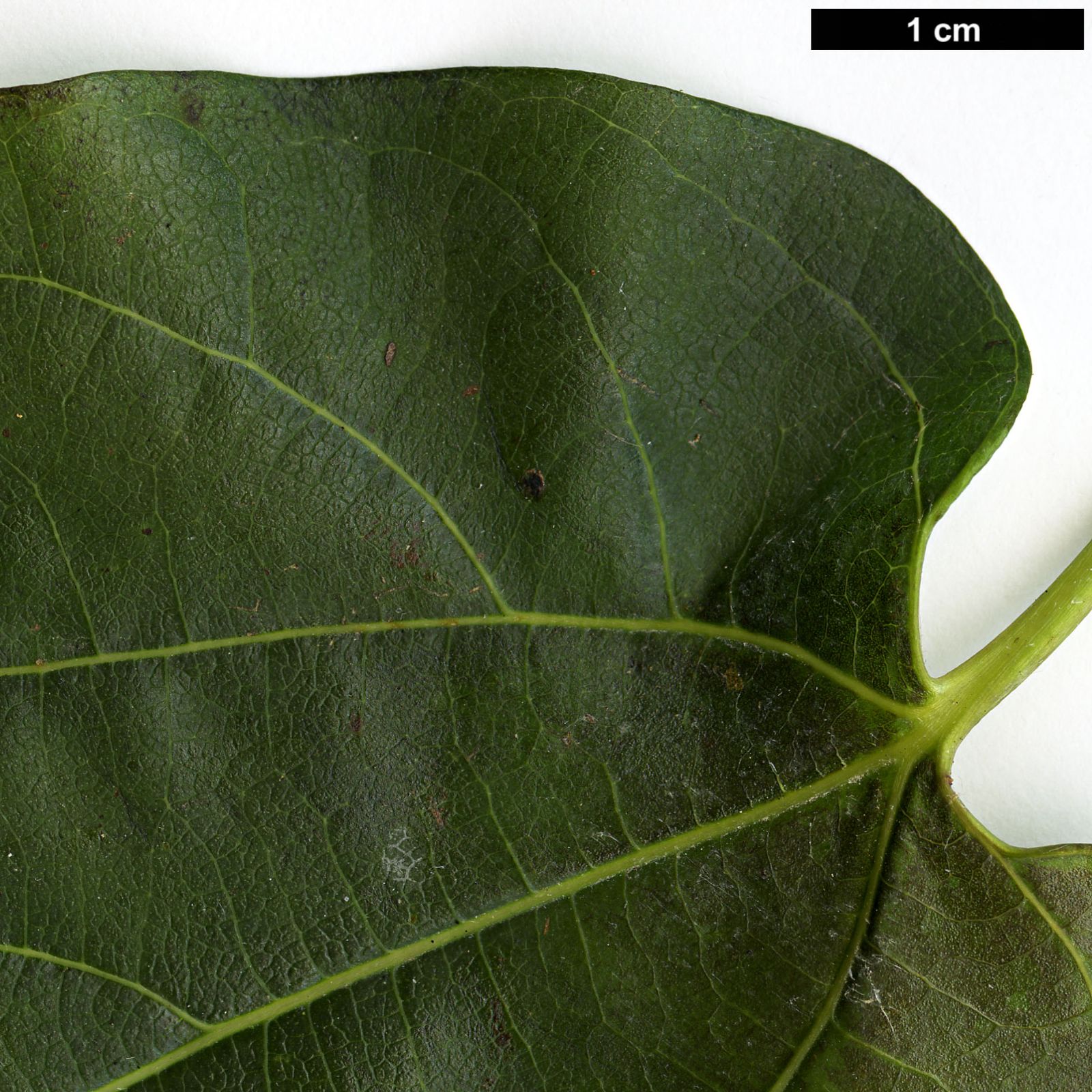

One further odd variant, this time with lobed leaves, was collected by Keith Rushforth (KR 6770) in a small, isolated high rainfall area of SE Tibet, above the Great Bend of the Yarlung Tsangpo (H. McAllister & T. Baxter, pers. comm. 2023). The asymmetric lateral lobes with rounded apices give the impression of pointing inwards (see image). A single male plant at Ness Gardens, Cheshire is growing reasonably; another is said to grow at Dawyck, Scotland (T. Baxter, pers. comm. 2023). Vegetative propagation is sorely needed.

var. heterophylla (Meisn.) H.P.Tsui

Synonyms

Lindera heterophylla Meisn.

Benzoim heterophyllum (Meisn.) Kuntze

Leaf blade usually not lobed, densely golden-sericeous when young (Cui & van der Werff 2008).

Distribution

- Bhutan

- China – Xizang, NW Yunnan

- India

- Nepal

Not all forms with unlobed leaves belong here, but plants in Britain said to derive from George Forrest’s F 29087 (see main text) seem to fit here (Lancaster & Rix 2019). At least one plant at Westonbirt (where it was first labelled Lindera cercidifolia, then L. praetermissa) has apparently set seed at some stage (D. Crowley pers. comm. 2023). The silky-hairy young leaves are distinctive and beautiful. Clarke (1988) mentioned plants at Wakehurst Place, Sussex, from a seed collection by Tony Schilling in E Nepal, where it is at the western limit of its range.