Abies fraseri

Sponsor

Kindly sponsored by

Sir Henry Angest

Credits

Tom Christian (2021)

Recommended citation

Christian, T. (2021), 'Abies fraseri' from the website Trees and Shrubs Online (treesandshrubsonline.

Genus

Common Names

- Fraser Fir

- Fraser's Balsam Fir

- Mountain Balsam Fir

- Southern Balsam Fir

- She Balsam

- Sapin de Fraser

- Frasers Tanne

Synonyms

- Abies balsamea subsp. fraseri (Pursh) E. Murray

Infraspecifics

Other taxa in genus

- Abies alba

- Abies amabilis

- Abies × arnoldiana

- Abies balsamea

- Abies beshanzuensis

- Abies borisii-regis

- Abies bracteata

- Abies cephalonica

- Abies × chengii

- Abies chensiensis

- Abies cilicica

- Abies colimensis

- Abies concolor

- Abies delavayi

- Abies densa

- Abies durangensis

- Abies ernestii

- Abies fabri

- Abies fanjingshanensis

- Abies fansipanensis

- Abies fargesii

- Abies ferreana

- Abies firma

- Abies flinckii

- Abies fordei

- Abies forrestii

- Abies forrestii agg. × homolepis

- Abies gamblei

- Abies georgei

- Abies gracilis

- Abies grandis

- Abies guatemalensis

- Abies hickelii

- Abies holophylla

- Abies homolepis

- Abies in Mexico and Mesoamerica

- Abies in the Sino-Himalaya

- Abies × insignis

- Abies kawakamii

- Abies koreana

- Abies koreana Hybrids

- Abies lasiocarpa

- Abies magnifica

- Abies mariesii

- Abies nebrodensis

- Abies nephrolepis

- Abies nordmanniana

- Abies nukiangensis

- Abies numidica

- Abies pindrow

- Abies pinsapo

- Abies procera

- Abies recurvata

- Abies religiosa

- Abies sachalinensis

- Abies salouenensis

- Abies sibirica

- Abies spectabilis

- Abies squamata

- Abies × umbellata

- Abies veitchii

- Abies vejarii

- Abies × vilmorinii

- Abies yuanbaoshanensis

- Abies ziyuanensis

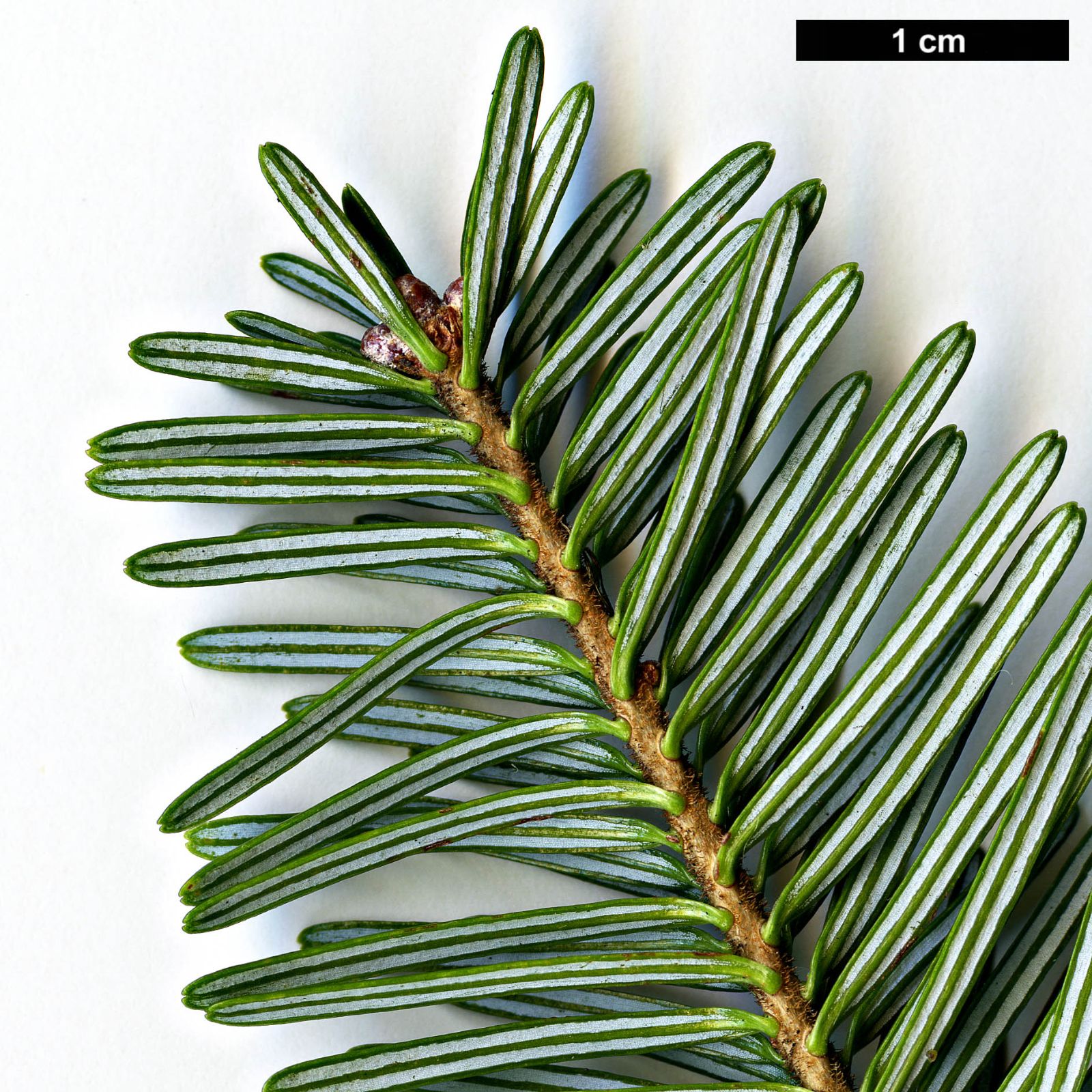

Tree 15–30 m tall, to <0.8 m dbh. Crown narrowly conical or columnar, often irregular in exposed locations, broad in sheltered solitary trees. Bark smooth, reddish-brown with prominent resin blisters on young trees; becoming grey-brown, rough, and scaly in old trees. First order branches long, ascending in the crown, spreading laterally in the lower part of the trunk, second order branches slender, spreading horizontally or assurgent. Branchlets slender, stiff, pale yellowish-grey or grey-brown at first, becoming duller and darker with age, shallowly grooved, densely pubescent for several years with short reddish hairs that can lend the branchlets a pinkish hue. Vegetative buds broad-ovoid, 4 × 3 mm, very resinous, bud scales dark red-brown but usually covered with yellowish resin. Leaves pectinate beneath the shoot, those of the upper rank forwards, somewhat assurgent, both ranks assurgent on coning shoots which can occur low down on young trees, 1–2(–2.5) cm × 2–2.2 mm, broadest near the apex, base twisted, apex obtuse (rarely emarginate, acute on coning shoots), dark green above with two whitish stomatal bands beneath, a scattering of stomata along the central groove above, especially near the apex. Pollen cones crowded, pendulous, 1 cm, yellow with red microsporophylls. Seed cones often densely set on branches, short-pedunculate, oblong-conical, tapering to obtuse apex, 4–8 × 2.4–4 cm, dark purple or bluish-purple at first, purple-brown at maturity; seed scales broad-flabellate to reniform, 0.8–1.2 × 1–1.5 cm at midcone; bracts obovate, conspicuously exserted almost obscuring the cone scales, yellowish at first, pale-brown at maturity. (Farjon 2017; Debreczy & Rácz 2011).

Distribution United States Scattered in the southern Appalachian Mountains in western North Carolina, eastern Tennessee, and south west Virginia.

Habitat Sub-populations are restricted to the Southern Appalachians at 1200–2150 m asl, the best stands usually on north facing slopes. The climate is characterised by cool, humid summers and cold winters with heavy snowfall. Occurring as pure stands at the highest points, but usually with Picea rubens, Betula papyrifera and Rhododendron catawbiense. Lower-elevation associates include Tsuga caroliniana, Betula alleghaniensis, Sorbus americana, Acer saccharum and Fraxinus caroliniana.

USDA Hardiness Zone 5

RHS Hardiness Rating H6

Conservation status Endangered (EN)

Fraser Fir was brought to the attention of botanical science by the Scottish plant collector John Fraser (1750–1811) who undertook several botanical explorations in eastern North America in his lifetime. Among his other notable introductions from the region are the eponymous Magnolia fraseri, and Rhododendron catawbiense (Lindsay 2005). He introduced his fir to cultivation in c. 1807 when he sent seed to Lee’s Nursery in Hammersmith, London. It was formally described a few years later and named in Fraser’s honour as Pinus fraseri, but it would not go down as one of his finer introductions. Bean managed to find it within himself to admit that ‘like A. balsamea, it is attractive when young’ but only after he had savaged it by saying ‘No silver fir ever introduced has proved of less value in English gardens than this, or shorter-lived’ (Bean 1976).

Perhaps if he had spent more time in Scotland Bean would have been kinder to A. fraseri – now as then it prefers the cooler, more humid Scottish collections to those of southern England, and besides being attractive when young it remains so for longer in climates to which it is better suited. Examples so attesting may be found in northern European collections, for example in the Gothenburg Botanic Garden, Sweden (pers. obs. 2019) and in the Woodland Garden at Ardkinglas, Argyll, UK (pers. obs. 2020). Fraser Fir can grow extremely quickly in youth, putting on over 60 cm in a single season, and it can also cone from a young age, adding to its value as a small ornamental tree. This is perhaps just as well as it has enjoyed a popularity boom in Europe in recent years as a species of Christmas tree. Most of this stock will of course be cut from field-grown trees, but a proportion will be offered for sale as ‘living trees’ in pots and then planted in gardens, so it doesn’t seem outlandish to suggest that Fraser Fir will follow A. nordmanniana in becoming an increasingly common sight in suburban gardens in western and northern Europe.

Even in optimum conditions, however, it would be unreasonable to expect Fraser Fir to remain attractive for more than perhaps 40 or 50 years, hence it will be important, where aesthetics are the only consideration, to be ruthless and not let them outstay their welcome, removing them before they begin their sharp decline to decrepitude (to borrow a favoured word from W.J. Bean). Fraser Fir has suffered substantially in the wild due to devastating attack by Balsam Woolly Adelgid (Adelges piceae), an invasive alien pest that was first recorded in wild populations in 1957, and this is also a problem in Christmas tree plantations in the USA, and in general cultivation in some parts of Europe, too (Farjon 2019). Another notable threat is the pathogen Phytophthora cinnamomi which has infested plantations in the USA and caused almost 100% mortality in young trees (Kobliha et al. 2013). Fraser Fir is worth over $100 M per annum to the Christmas tree industry in North Carolina alone, hence growers have sought to circumvent this problem by hybridising A. fraseri with other species that have demonstrated resistance to P. cinnamomi, notably the Mediterranean species A. cephalonica and A. cilicica (Kobliha et al. 2013).

Some important introductions to ex-situ conservation collections have been made in recent years. Most notable in a UK context are those of Bedgebury National Pinetum, introduced in 2006 under various numbers assigned to the collector code CRDL, which received a broad distribution. Being a species that favours cooler northern regions even in a UK context, large numbers were sent for onward distribution by the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. There are now young trees in multiple Scottish collections including Benmore and Dawyck Botanic Gardens, and in the north of England at the University of Durham Botanic Garden (BG-BASE data 2020). Given the short-lived nature of the species in cultivation, though, such collections can only be seen as a short-term insurance policy, though clearly still of great value.

Several cultivars have been selected; most are dwarfs, and all appear confined to North American cultivation. A hybrid between Fraser and Balsam Fir is discussed under A. balsamea.

Dwarf Cultivars

Although there are not nearly so many registered A. fraseri cultivars as there are in A. balsamea, most that do exist are dwarfs. Several of them are quite alike:

- ‘Blue Bonnet’ Distinguished by its strongly glaucous leaves, ultimately a dwarf conical tree to 1.5 × 1 m in ten years. Found as a seedling in a Christmas tree plantation in 1987

- ‘Brandon Recker’ Extreme dwarf of dense habit and slow growth

- ‘Caerulea’ A low, spreading shrub with glaucous leaves, quite vigorous

- ‘Fantasticooli’ A conical selection of slow growth, ultimately a very small tree

- ‘Flynn’s Flash’ A dwarf version of the species with leaves tipped yellow

- ‘Ford WB’ A flat-topped extreme dwarf

- ‘Franklin’ Narrowly conical selection derived from a witches’ broom, to 1 m in ten years

- ‘Gee’ Extreme dwarf of irregular habit

- ‘Julian Potts’ Extreme dwarf of irregular habit

- ‘Kline’s Nest’ Forming a dwarf plant wider than tall, of compact habit with needles shorter than typical for the species, and inclined to produce seed cones once established

- ‘Kostelec’ Extreme dwarf growing wider than tall

- ‘Mount Kisco’ An extreme dwarf

- ‘Palmeri’ Extreme dwarf growing wider than tall

- ‘Piglet’s WB’ Extreme dwarf of low, spreading habit

- ‘Raul’s Dwarf’ Forming an upright, broad shrub to 60 × 45 cm in ten years

- ‘Reeseville Ridge’ A recent selection of fastigiate habit forming a very narrow column. Larry Hatch likens it to a Christmas tree being ‘bagged up’ by the vendor, an apt description!

(Auders & Spicer 2012; Hatch 2021–2022).

'Frederick'

A narrowly columnar form selected by Don Frederick of Pennsylvania in the 1970s (Auders & Spicer 2012). It may be distinguished from the relatively new columnar selection ‘Reeseville Ridge’ (see Dwarf Cultivars) by its first order branches being pendulous; in ‘Reeseville Ridge’ the first order branches are fastigiate (Hatch 2021–2022).

'Prostrata'

Forming a wide-spreading, low-growing plant, up to 4 m across and less than 1.5 m tall. Raised in Massachusetts in 1916 (Auders & Spicer 2012).