Chionanthus virginicus

Sponsor

Kindly sponsored by

a member of the International Dendrology Society

Credits

Julian Sutton (2022)

Recommended citation

Sutton, J. (2022), 'Chionanthus virginicus' from the website Trees and Shrubs Online (treesandshrubsonline.

Genus

Common Names

- Fringetree

Synonyms

- Chionanthus henryae H.L. Li

- Chionanthus virginicus var. maritimus Pursh

- Chionanthus virginicus var. montanus Pursh

Infraspecifics

Other taxa in genus

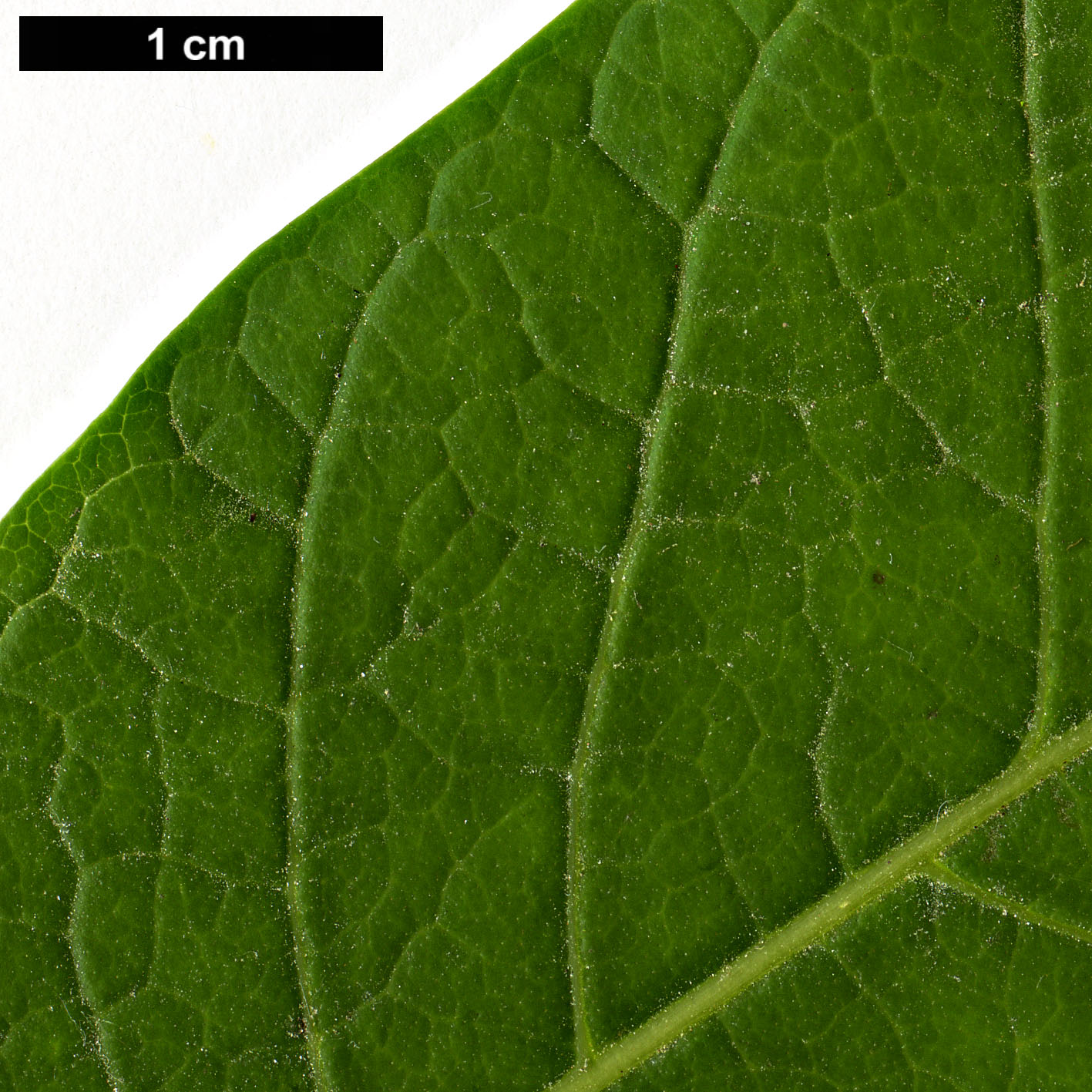

Large shrub or small tree, typically with open, spreading habit, to 10(–12.5) m, deciduous. Bark grey, smooth at first, ultimately slightly ridged. Branchlets stout and stiff, variably hairy, rich purple-brown in some plants. Leaf blade 5–20 × 2–9 cm, ovate, oblong or obovate; base cuneate; margins entire; apex acute or somewhat acuminate; upper surface glossy mid- to dark green, with downy midrib; lower surface paler green, downy, especially on the veins. Petiole 0.4–2 cm, downy. Plant normally functionally dioecious. Inflorescence a somewhat pendent cyme, axillary in the previous year’s nodes, 10–20 cm. Bracts conspicuous, often leaf-like. Flowers slightly fragrant; corolla white, lobes strap-shaped, 1.5–3(–4) cm × 1–3 mm; anthers with prolonged tips. Drupe ovoid, 1–1.5 cm, dark blue with a powdery bloom. Flowering late spring to early summer, but with wide geographical variation (March–)May–June(–July); fruiting late summer, (July–)August–September(–October) (United States). (Dirr 2009; Cullen et al. 2011; Hardin 1974; Gill & Pogges 1974).

Distribution United States Broadly southeastern, from Massachusetts south to Florida and Texas

Habitat Moist woods and hillsides, stream banks, occasionally rocky bluffs.

USDA Hardiness Zone 3-9

RHS Hardiness Rating H5

Conservation status Least concern (LC)

With its fluffy white flower heads and dark blue fruits which resemble small damsons, Chionanthus virginicus is potentially a highly attractive deciduous garden shrub or small tree, considered by its enthusiasts underutilized even in its native North America (Nicholson 1990). There are, however, reasons why it is less than mainstream. A difficult species to propagate, it is also functionally dioecious, meaning that multiple individuals must be planted for the best floral and fruiting display. Moreover, it flowers and fruits best in a continental climate; performance is less impressive in the more maritime climates of the Pacific Northwest and northwestern Europe. Despite this, Bean (1976) concluded that ‘There is nothing like it among flowering shrubs except its Asiatic ally [C. retusus].’

Among the deciduous, temperate zone species of Chionanthus (all those described here) C. virginicus is distinguished from the East Asian C. retusus by inflorescence position. In C. virginicus they are axillary in the previous year’s nodes, while in C. retusus they are terminal on current year’s growth. It was described early in the era of scientific plant classification by Linnaeus (1753), material having been introduced to Europe earlier that century. A variable species, there have been several attempts to make sense of patterns of variation by describing segregate species and varieties. Only one such species is widely recognized today, C. pygmaeus (q.v.), an endangered Florida endemic distinguished from C. virginicus by being usually a shrub to 2 m (rarely 4 m) (versus shrub or small tree to 10 m); its shorter corolla lobes, about 1 cm long (versus 1.5–3 cm); its blunt or acute, but not prolonged anther tips (versus prolonged); its larger drupe, 2–2.5 cm long (versus 1–1.5 cm), and its elliptic leaves, towards the small end of the range seen in C. virginicus, 3–9 cm long (Small 1924; Hardin 1974).

Other taxa described over the years are now usually sunk into synonymy with C. virginicus, although some occasionally appear in the catalogues of arboreta and botanic gardens. C. henryae H.L. Li (leaves coriaceous, smooth above, to 8 cm long; petioles 4–6 mm; anthers with connective abruptly projected and blunt tipped; Florida, Arkansas, Alabama, Georgia – Li 1966) has been rejected by almost all contemporary American workers, following Hardin (1974). Aiton (1789) distinguished two varieties based on material cultivated in Britain, var. angustifolius Aiton (leaves lanceolate) and var. latifolius Aiton (leaves ovate-elliptic). Working in North America with a wider range of material, Pursh (1814) distinguished var. maritimus Pursh (leaves obovate-lanceolate, papery, pubescent; inflorescence lax; boggy coastal woods) and var. montanus Pursh (= subsp. montanus (Pursh) A.E. Murray; leaves elliptic-lanceolate, coriaceous, glabrous; inflorescence dense; mountains); a type variety var. virginicus appears not to have figured in Pursh’s scheme. Exploring variation from a horticulturist’s standpoint, Dirr (2009) tentatively distinguished a southern (Florida) form with narrower, more lustrous, dark green leaves than northern plants.

This is a functionally dioecious species. While all flowers have both stamens and carpels, male trees have much smaller, sterile carpels while the anthers of females produce no pollen (Gleason & Cronquist 1991). On some plants, though, occasional flowers may have both female and male function (Nicholson 1990). Insects, perhaps mainly bees, seem to be the pollinators (Wadl et al. 2022).The combined mass of strap-shaped petals across the entire inflorescence is what makes the plant so showy in the garden. Petals tend to be longer in males, which are hence considered more desirable in flower (Nicholson 1990; Dirr 2009). Both sexes have a light scent, which Nicholson (1990) describes as ‘spicy’ and ‘privet-like’, although some complain of unscented clones in the nursery trade (Wasowski 1994). Flowers emerge more or less with the young leaves, so their ornamental effect changes as the flowering season progresses and leaves expand. In its wild range, flowering starts as early as March in the deep South, May–June further north (Gill & Pogges 1974). The possibility of a pink or red flowered variant continues to excite enthusiasts (Dirr 2009). The rumour of its existence seems to stem from a comment in B.S. Barton’s 1812 expansion of Clayton & Gronovius’ Flora Virginica (fide Nicholson 1990, who considered it lost), and it seems likely that contemporary claims by non-specialist gardeners to have seen it result from confusion with red-flowered forms of Loropetalum chinense, marketed in North America as Chinese Fringe Flower.

The dark blue fruits are a further attraction, although reliable fruit set requires both male and female trees. The fleshy part of the drupe is soft at maturity, with usually a single hard ‘stone’, the whole structure resembling an olive. Dispersed by a wide range of birds and mammals in the wild (Gill & Pogges 1974), they are too bitter to be considered as human food, and while it is easy to find indirect reports of the unripe fruit being pickled, firsthand accounts and reliable recipes are elusive. Preparations of roots or bark were used to treat skin wounds and irritation both by indigenous peoples of the Southeast and European settlers in Appalachia (Moerman 2003; Gill & Pogges 1974). Uses by modern herbalists and homeopaths seem much more diverse.

The Fringetree is well established in mainstream horticulture away from the driest and coldest areas of North America, and is heavily represented in collections. Usually found in the wild in moister places, it suits a range of well drained soils, both acidic and alkaline, in sun or light shade (Dirr 2009). Sometimes suggested as a specimen plant, Nicholson (1990) considers that its rather late leafing and flowering can make it look awkward in spring, recommending it for the edges of properties, even as a hedge (since it flowers on old wood, timing of hedge cutting would be critical, and annual trimming would almost certainly be incompatible with fruiting). Flowering is most spectacular in more continental climates. Nicholson (1990) describes a lawn specimen in Shelburne Falls, MA (USDA zone 5), 8 m tall with spread of 10 m, known to stop busloads of Japanese tourists when in full flower. Autumn leaf colour is another potential attraction, sometimes merely yellowish, but a good yellow in some specimens (Dirr 2009).

Introduced to Europe in 1736 by Peter Collinson of London (Aiton 1789), presumably from seed collected by John Bartram, by the late 19th century Robinson (1898) could state that while ‘in some old English gardens there are fine specimens, […] it is rarely met with in modern gardens’. This might in part be due to its relatively poor flowering in more maritime Western Europe compared with Eastern North America and Central Europe (Bean 1976). Available from specialist nurseries but not commonly planted, conversations around preparation of this account revealed that even some serious, plantsmanly British gardeners had never heard of it, some believing they had misheard ‘Chimonanthus’. The Tree Register (2022) records few examples, none of remarkable size, although its borderline status between tree and shrub may result in under-recording here; the British champion, planted 1978 in Ray Wood at Castle Howard, North Yorkshire, measured a mere 4.5 m × 52 cm in 2021. Fringe Tree enthusiast Michael Dirr’s (2009) contention that it is ‘considered by the British to be one of the finest American plants introduced into their gardens’ seems an overstatement. Although widely hardy, records from continental collections are similarly sparse.

Several cultivars have been selected in the later 20th and 21st centuries, mostly in North America and mainly for free-flowering habit or crown form (Dirr 2009). Most are male. A study of geographical patterns of genetic variation in wild plants suggested that there are unlikely to be small, local pockets of diversity which might be missed by breeders seeking novel breeding stock (Wadl et al. 2022). In addition to those listed, a number of named cultivars seem to have little or no distribution, most interestingly ‘Pat’s Variegated’ (irregular yellow variegation, reasonable flowering; Juniper Level Botanic Garden, NC before 2004 – Hatch 2015) and ‘Black Stem’ (ornamental black young stems – Buchholz & Buchholz Nursery 2022).

Seed shows ‘double dormancy’; sown in autumn it appears to germinate in the second spring. In fact, a root develops during the first extended warm period, the shoot not appearing until after a subsequent cold spell (Dirr 2009). Accelerated techniques using embryo culture have been developed (Chan & Marquard 1999). Cuttings have traditionally been considered difficult to root, although American growers mostly prefer this to grafting (Dirr 2009). European and sometimes American nurserymen have grafted onto Fraxinus ornus and F. excelsior; the resulting plants may be short lived (Huxley, Griffiths & Levy 1992), and suckering from the rootstock is an issue (Dirr 2009). Seed-raised C. virginicus stock is probably the better option for propagating cultivars. Layering is another possibility, in autumn or spring (Huxley, Griffiths & Levy 1992).

'CV1049'

Synonyms / alternative names

Chionanthus virginicus SERENITY®

Broader, denser canopy than typical seedlings; good vigour and flowering. Selected before 2022 by Select Trees, Georgia, whose Chionanthus cultivars are selected for comparative ease of propagation by cuttings, and are sold on their own roots (Select Trees 2022; Broken Arrow Nursery 2022).

'CVSTF'

Synonyms / alternative names

Chionanthus virginicus PRODIGY®

Rounded crown; shiny, dark green, leathery leaves which remain healthy-looking through the summer; heavy flowering. Selected and distributed in North America before 2009 by Select Trees, Georgia (Dirr 2009; Select Trees 2022).

'Dirr'

Synonyms / alternative names

Chionanthus virginicus Dirr Clone

A vigorous tree-forming clone, claimed as the fastest grower in nursery production; a male, with dark green leaves, larger than those of ‘CV1049’, ‘Spring Fleecing’ or ‘White Knight’ (Dirr & Warren 2019). Selected by Michael Dirr, GA before 2019. Listed by Dirr & Warren (2019) as Dirr Clone (which would not be admissable as a formal cultivar name); usually labelled ‘Dirr’ by North American nurseries.

'Emerald Knight'

Upright habit, 4.5–6 m tall, less in width; long, dark green, glossy leaves; male. Raised before 2009 by Brian Upchurch, Highland Creek Nursery, NC (Dirr 2009). ‘Tough to propagate’ (Broken Arrow Nursery 2022).

'Floyd'

Upright habit and dense flowers; male. Originated about 1945 at the Sonnemann Experimental Garden, IL; named 1969 by Joe McDaniel in honour of W. Floyd Sonnemann, and distributed thereafter (Dirr 2009; Jacobson 1996). Probably never a common plant.

'Groenendaal'

Compact, tidy crown; a free-flowering male. Selected 1994 at Arboretum Wespelaar, Belgium: a plant raised by Philippe de Spoelberch in 1972 from seed collected at Arboretum Groenendaal, Belgium (Arboretum Wespelaar 2022). Distributed in Europe.

'Spring Fleecing'

Flowering heavily from a young age, male; glossy, narrow leaves. Selected before 2009 by Sam Allen, Tarheel Native Trees, NC (Dirr 2009; Broken Arrow Nursery 2022).

'White Knight'

Flowering heavily from a young age; shiny, leathery leaves. Selected before 2012 by Alan Jones, Manor View Farm, MD, where it is propagated by chip budding, presumably onto seed-raised C. virginicus stocks (Alexander et al. 2012; Broken Arrow Nursery 2022).