Liquidambar orientalis

Sponsor

Kindly sponsored by a member of the International Dendrology Society.

Credits

Owen Johnson (2021)

Recommended citation

Johnson, O. (2021), 'Liquidambar orientalis' from the website Trees and Shrubs Online (treesandshrubsonline.

Infraspecifics

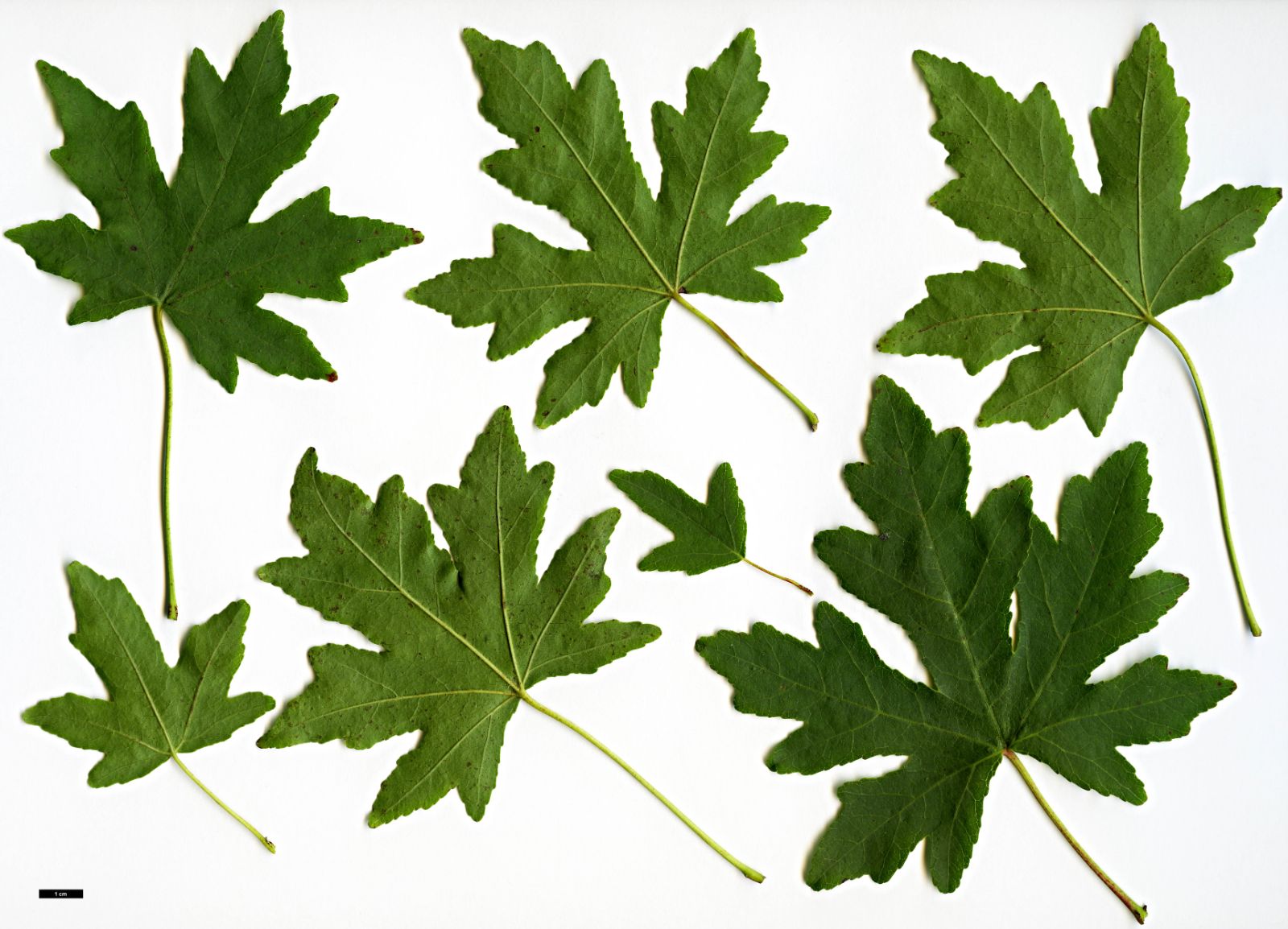

Tree to 30 m tall, often with a long bole. Bark dark grey brown, soon quite deeply fissured into small oblong plates. Shoots glabrous, usually lacking corky projections; buds pointed, many-scaled, glabrous. Leaves 4–8 × 6–9 cm, usually with 5 deep narrow lobes, which are coarsely glandular-toothed and generally lobulate; both surfaces normally glabrous; petiole 3–5 cm. Fruit-balls small (c. 2.5 cm wide), their surface smooth in between the conical twisted projection of each seed. (Bean 1981).

Habitat In pure stands on flood-plains and in deltas that flood in spring, or on drier mountainsides with other trees, to 1800 m asl.

USDA Hardiness Zone 7

RHS Hardiness Rating H5

Liquidambar orientalis is one of Europe’s rarest trees. In its centre of distribution in southwestern Turkey pure stands have been reduced from 6,000–7,000 ha in the 1940s to about 1,350 ha today, as forests were cleared for agriculture and rivers were dammed; since the 1980s there has been a limited recovery, with the establishment of nature reserves, seed stands, and clonal seed orchards (European Forest Genetic Resources Programme 2021).

The extraction of an aromatic resin from the species’s inner bark used to be an important local industry; outer bark was partially stripped from the trunks in summer, and the tree was tapped. Distilled and mixed with oil, the resin was sold under the names of storax oil, styrax levant, asiatic storax, or balsam storax; it was an ingredient in the old cough remedy Friars Balsam and it continues to be used as a flavouring, for example in chewing gum, as a stabiliser in baking, in soaps, and in cosmetics. The hydrocarbon styrene, employed in polystyrene and styrofoam, was originally isolated from this resin (Plants for a Future 2021), although its name was derived from that of the unrelated genus Styrax. For many years it was assumed that Styrax officinalis, which also exudes an aromatic resin and which is widely distributed in the east Mediterranean region, was the source of storax, but L. orientalis has been convincingly shown to be the true source.

L. orientalis was introduced to France in the mid-18th century by Charles-Claude de Peyssonnel, Consul at Smyrna, and was obtained in 1759 by Philip Miller for the Apothecaries’ Garden (now the Chelsea Physic Garden) in England (Hsu & Andrews 2005). A specimen at Woburn in Bedfordshire, planted in 1838, blew down in 1934 (Hsu & Andrews 2005).

Most of the trees that L. orientalis grows alongside – Platanus orientalis (with its similarly shaped but much larger leaves and similar-looking but much softer fruit-balls), Quercus cerris, Fraxinus angustifolia, Pinus brutia and Cotinus coggygria – thrive in the climate of northwest Europe; only Alnus orientalis is something of a failure, growing fast but seldom surviving very long. The Oriental Sweet-gum itself seems relatively long-lived and hardy, but it grows very slowly and forms a low, twisted, twiggy and bushy tree. Oddly, it seems no more at home in the relative warmth of London than it does at Bodnant in north Wales, where one has a short trunk 52 cm thick (Tree Register 2021), or in the Irish lowlands, where a single-boled specimen 12 m tall was reported at St Patrick’s College in Kildare for the Tree Register of Ireland project in 2000 (Tree Register 2021), while the UK and Irish champion was discovered by Donald Rodger in 2017 in a private garden in Edinburgh and is 13.5 m × 60 cm dbh (Tree Register 2021), having thoroughly outgrown any Scottish examples of the supposedly more adaptable L. styraciflua.

With its poor performance and relatively muted autumnal browns and oranges, it is understandable that this species has remained confined to just a few big gardens and collections in northern Europe, and the cultivated population probably contains relatively low genetic diversity, notwithstanding several quite recent introductions to specialist collections. At Wakehurst Place, a tree from the collection KARH 8821 (1996) had grown relatively well to 7 m by 2010 (Tree Register 2021). At Arboretum Trompenburg in the Netherlands, a specimen grown from seed collected near Izmir in 1986 has an erect habit (Hsu & Andrews 2005). Hsu and Andrews also reported young, wild-collected trees at Dr A. De Clercq’s garden in Nevele, Belgium, and in that country’s National Botanic Garden at Meise. It does now seem likely that climate change will make L. orientalis a more attractive prospect, at least in southeast England and the near Continent, where it is hardy.

Around the western Mediterranean, by contrast, L. orientalis luxuriates, growing a long straight bole and reaching a great age. The oldest, at the Orto Botanico at Bologna in northern Italy, was mentioned by Bean (Bean 1981) and was still extant in 2017 when large gaps led to the hollow interior of its huge bole, which was 161 cm thick (monumentaltrees.com 2021). Another, at the Jardines del Principe at Aranjuez in Spain, is 32 m × 139 cm dbh (monumentaltrees.com 2021).

In the United States, this tree has understandably failed to compete with the native Sweet-gum in popularity; American sources who describe it as small and shrubby are presumably reporting its performance in northern Europe, as there is no reason why it should not thrive in California and the southeastern states. A reasonably well-grown young tree is on the campus of Oregon State University at Corvallis (Oregon State University 2020), while online photos suggest that it is hardy enough to survive at the Morton Arboretum in Illinois, and it is also cultivated in the promising conditions of Blake Garden, Kensington, California.

In Australia, the species is sold by Yamina Rare Plants, with the customary comment that it is a ‘small bushy tree’. One photo shows a substantial tree in the Centennial Parklands in Sydney, though with heavy, low limbs that recall its stunted habit in northern Europe.

Some younger trees in England, which are growing relatively well, show the dense tufts of axillary hair under the leaves’ main vein joints that are supposed to be a feature of L. styraciflua. The possibility should be considered that these are accidental hybrids, raised from seeds imported from some warmer nursery where both species happen to grow within pollinating range. A similar origin is sometimes suggested for the L. styraciflua cultivars ‘Worplesdon’ and ‘Stared’ (q.v.), whose leaf shape certainly recalls that of the Turkish Sweetgum. Michael Dirr (Dirr 2009) has also suggested that a lost evergreen cultivar of L. styraciflua from California, ‘Fremont’, may also have been a hybrid, perhaps with L. orientalis.

'Ann Spencer'

Liquidambar orientalis ‘Ann Spencer’ was found by the lady commemorated by its name, and was distributed by Don Howse, Porterhowse Nursery, Sandy, Oregon, from about 1999. It has proven to be a small, slow-frowing tre with corky twigs. In spring the leaves emerge dark red but become green in summer, before becoming dark purple to purple-black in autumn. They persist well on the tree (Bolscher & Vergeer 2016). It is now well established in the nursery trade in Europe.

'Ivy Hatch'

Synonyms / alternative names

Liquidambar orientalis 'Maurice Foster'

Liquidambar orientalis 'M. Foster'

Liquidambar orientalis ‘Ivy Hatch’, selected by Maurice Foster, bears the name of the village in Kent, UK, where his garden at White House Farm is located. It forms a small, wide-spreading tree, with densely corky twigs and branches. The small leaves are as broad as they are wide, and turn yellow to dark yellow-orange in autumn. It is said to be hardier than unselected L. orientalis, but the shoots remain vulnerable to spring frosts (Bolscher & Vergeer 2016).

Only recently given a valid clonal name, it has been previously distributed in the UK and continental Europe as L. orientalis ‘Maurice Foster’ or ‘M. Foster’ (J. Aldridge pers. comm.)