Nothofagus solandri

Sponsor

Kindly sponsored by

Col. Giles Crisp

Credits

Owen Johnson (2020)

Recommended citation

Johnson, O. (2020), 'Nothofagus solandri' from the website Trees and Shrubs Online (treesandshrubsonline.

Genus

Common Names

- Black Beech

Synonyms

- Fagus solandri Hook. f.

- Fuscospora solandri (Hook. f.) Heenan & Smissen

Other taxa in genus

- Nothofagus alessandrii

- Nothofagus alpina

- Nothofagus antarctica

- Nothofagus betuloides

- Nothofagus × blairii

- Nothofagus cliffortioides

- Nothofagus cunninghamii

- Nothofagus × dodecaphleps

- Nothofagus dombeyi

- Nothofagus fusca

- Nothofagus glauca

- Nothofagus gunnii

- Nothofagus × leonii

- Nothofagus macrocarpa

- Nothofagus menziesii

- Nothofagus menziesii × obliqua

- Nothofagus moorei

- Nothofagus nitida

- Nothofagus obliqua

- Nothofagus pumilio

- Nothofagus truncata

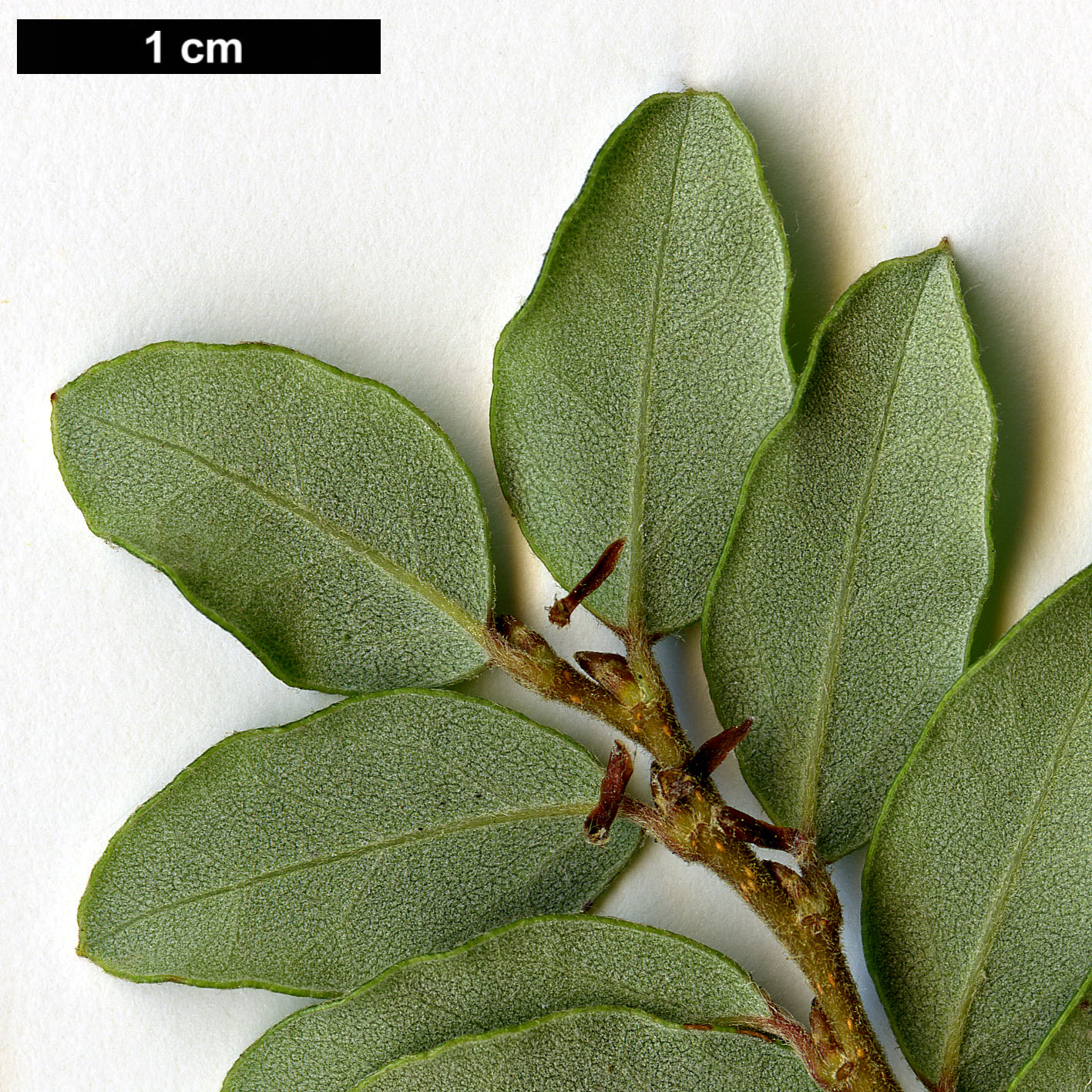

A tree to 30 m tall, often with an irregular or rounded habit and with many slender limbs. Bark dark grey, smooth into old age or finely and horizontally wrinkled; ultimately with rugged ridges in the wild. Shoots slender (1 mm thick), dark reddish, densely and closely pubescent. Buds c. 4 mm, conic, reddish. Leaves evergreen (persisting for 2 years), oval to ovate, the tip rounded but sometimes apiculate; 10–15 × 7–8 mm, glabrous and glossy above (blackish-green in winter), paler beneath and variably grey-pubescent; petiole 1–2 mm; lateral veins in 3 or 4 pairs, only clearly visible on the underside. Male flowers singly or in groups of 2–3; stamens 8–17; female flower densely pubescent, c. 2 × 1.5 mm. Cupule usually 3-valved, c. 6 mm long; valves with 3 or 4 entire transverse plates. Nutlets usually 3, winged. (Nothofagus 2007–2008; Bean 1976; Poole 1949).

Distribution New Zealand Absent only from the far north of the North Island, and the south of the South Island where it grades into or gives way to N. cliffortioides.

Habitat Lower-altitude forests; forming pure stands in drier sites with less fertile soils; grading into N. cliffortioides or replaced by it at higher altitudes.

USDA Hardiness Zone 7-8

RHS Hardiness Rating H5

Conservation status Least concern (LC)

Taxonomic note The species was named by Hooker to honour the Swedish botanist Daniel Solander; contrary to Desmond Clarke’s (1988) assertion that it should be ‘corrected’ to solanderi, but as it is seen as an intentional Latinization (Solandrus), the epithet is is not correctable (Turland et al. 2018, R. Govaerts pers. comm. 2020). The variant has however been quite widely adopted in horticulture and is used by the website nothofagus.free.fr.

Nothofagus solandri forms a cline with N. cliffortioides, which replaces this species at higher altitudes and in the southern end of its range. As solandri gives way to cliffortioides trees exhibit progressively more triangular leaves with down-curled sides and uprearing tips; any other distinguishing features are very subtle. It might therefore seem sensible to consider N. cliffortioides as a variety of N. solandri, as was proposed by A.L. Poole in 1958 (Poole 1958), but the current account follows most contemporary New Zealand botanists, such as R. D. Smissen (Smissen et al. 2014), and treats the two forms as separate species. Genetic studies by Smissen et al. imply a large amount of hybridisation, but also show that geographically distant populations of both parent forms can be genetically quite uniform, suggesting that N. solandri and N. cliffortoides may have evolved in relative isolation and more recently have increasingly interbred (Smissen et al. 2014). The gradation is similar to that reported between the plane-leaved Pittosporum colensoi and the wavy-leaved P. tenuifolium and between a number of other pairs of New Zealand taxa, all of which are conventionally viewed as ‘good’ species.

In cultivation in the UK and Ireland both these Nothofagus perform similarly, though nearly three quarters of the 150 specimens on the Tree Register are referrable to N. cliffortioides. The lower habit of N. cliffortioides in harsh conditions in the wild ceases altogether to be a distinguishing feature when both species are grown side-by-side in sheltered gardens. The first evidence for the group’s cultivation in Britain seems to have been a young tree growing at Nymans in West Sussex in 1917 (Bean 1976); this was probably the big example in the walled garden which blew down in 1987 and was generally considered to be N. cliffortioides (Tree Register 2020). A tree of similar size and age at Wakehurst Place, a few miles away, was identified as N. solandri; this was destroyed in the same storm. A 1922 planting in Gores Wood at Borde Hill, another great garden in the same part of the western High Weald, was catalogued as N. cliffortioides in 1932, but had the flat oval leaves characteristic of N. solandri when examined in 2010, when it was a slender tree 18 m tall (Tree Register 2020).

Currently, the UK and Ireland champions for N. solandri grow in mild and humid western gardens: 20 m × 103 cm dbh (at 1 m) in 2017 at Benmore Botanic Garden in Argyll, Scotland; 21 m × 95 cm dbh in 2016 at Rowallane in Co. Down, Northern Ireland (and not to be confused with the big N. cliffortioides here); and 26 m × 69 cm dbh in 2014 at Tregrehan, Cornwall (where a pair of trees are both exactly this size). Specimens recorded as N. solandri and which show the species’ tolerance of almost the whole range of growing conditions in Britain include trees of 14 m × 79 cm dbh in 2014 at the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh; an old 10 m tree in 2016 at The Hollies, now a public park in suburban Leeds; a 12 m tree in 2005 planted in 1959 by Hugh Johnson at Saling Hall in Essex – one of the driest places in England – and a 16 m tree at Keir House in Stirling on the fringe of the Scottish Highlands. Another tree, 16 m tall in 2015 at Mount Usher in Co Wicklow, Ireland, has thrived in a slightly alkaline soil. (Tree Register 2020).

The tiny leaves, like green fingernails, and the attractive habit with its crimped layers of foliage, create an ornamental effect unlike almost any other large tree’s, and yet in common with so many Nothofagus the Black Beech’s cultivation as an exotic ornamental seems until recently to have been effectively confined to the UK and Ireland. Growth looks as if it should be slow – and is reportedly so in the wild – but a sapling germinated by the late John Purse and planted by the author in 2017 in a moist, woodland setting in his local public park (Alexandra Park in Hastings, East Sussex) has so far maintained a growth-rate of just over a metre per year, scarcely slowing down through the winter months. After a dry or windy winter, however, cultivated trees in greater exposure can be almost leafless and will look very sorry for themselves; new leaves are grown in spring but as the leaves are meant in the wild to last for two years, these stressed specimens will never look really luxuriant. (N. cliffortioides, as a high-altitude specialist, should presumably be better adapted to such conditions, but this is not really noticeable in cultivation; the problem is probably less one of absolute exposure than of water-loss during cold dry easterlies.)

Young trees are now flourishing in New Zealand Forest area of the Washington Park Arboretum in Seattle (images at: https://davesgarden.com/guides/pf/showimage/183918/), where they get well-watered through the regular summer drought experienced by the Pacific Northwest.